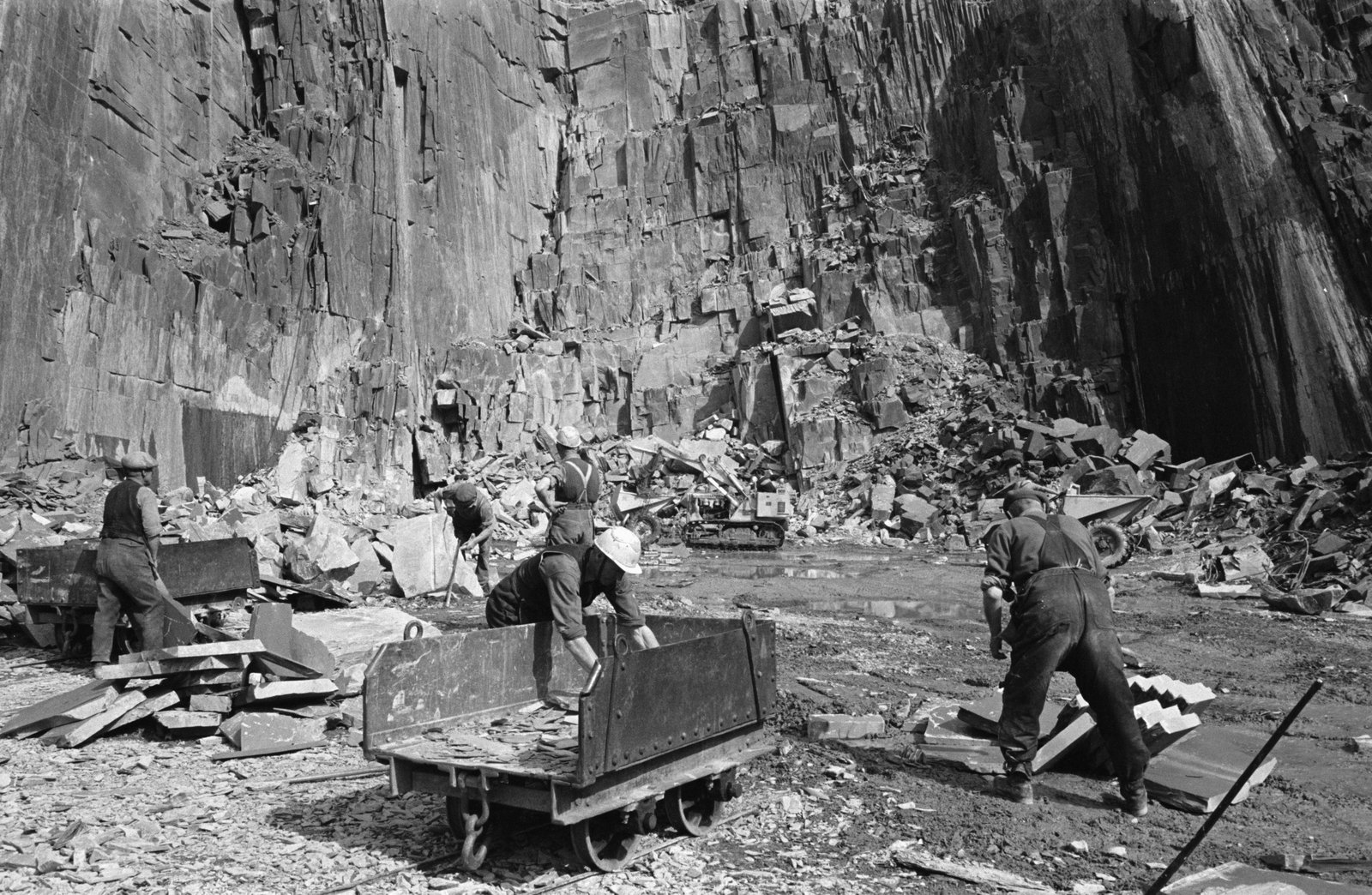

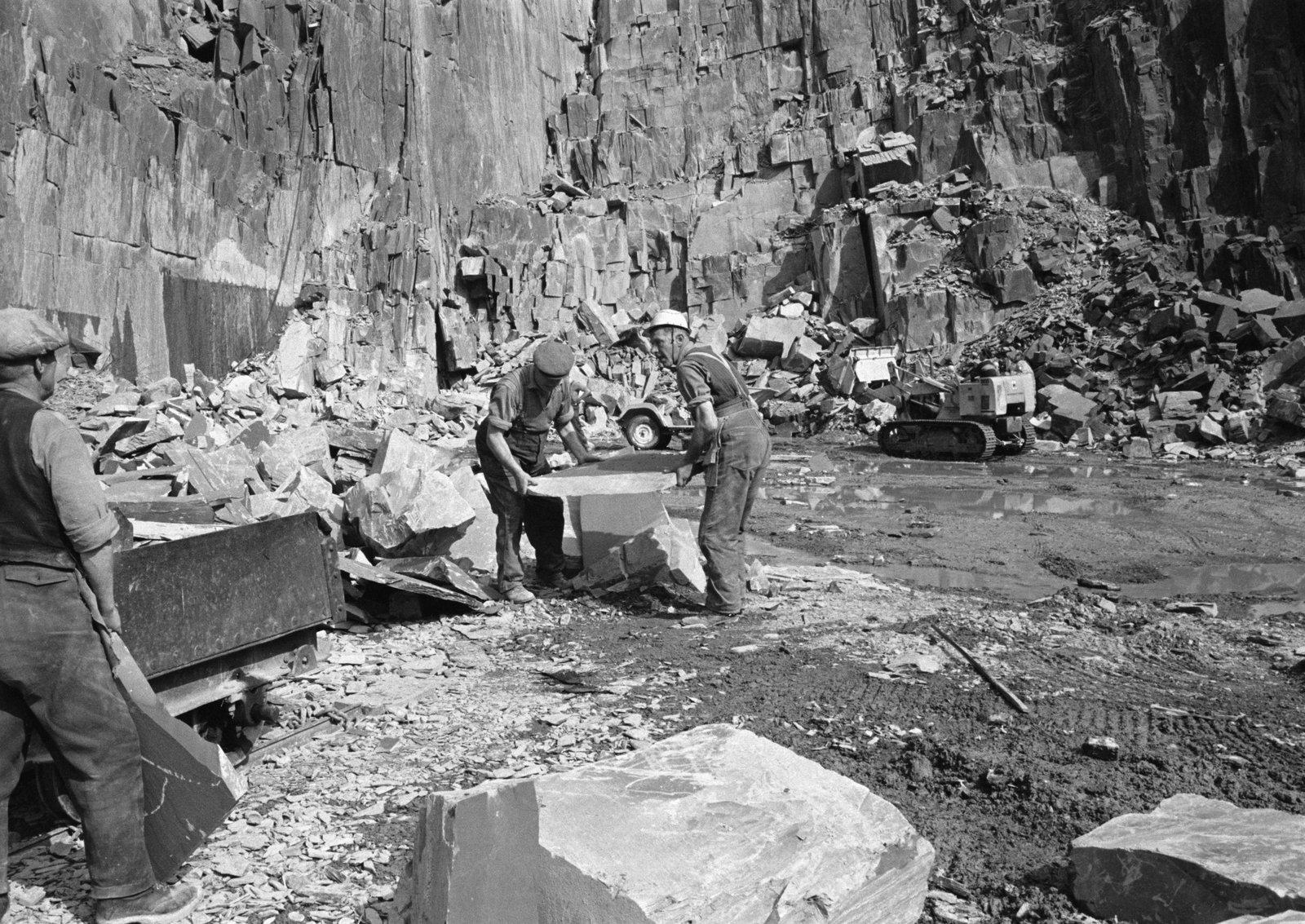

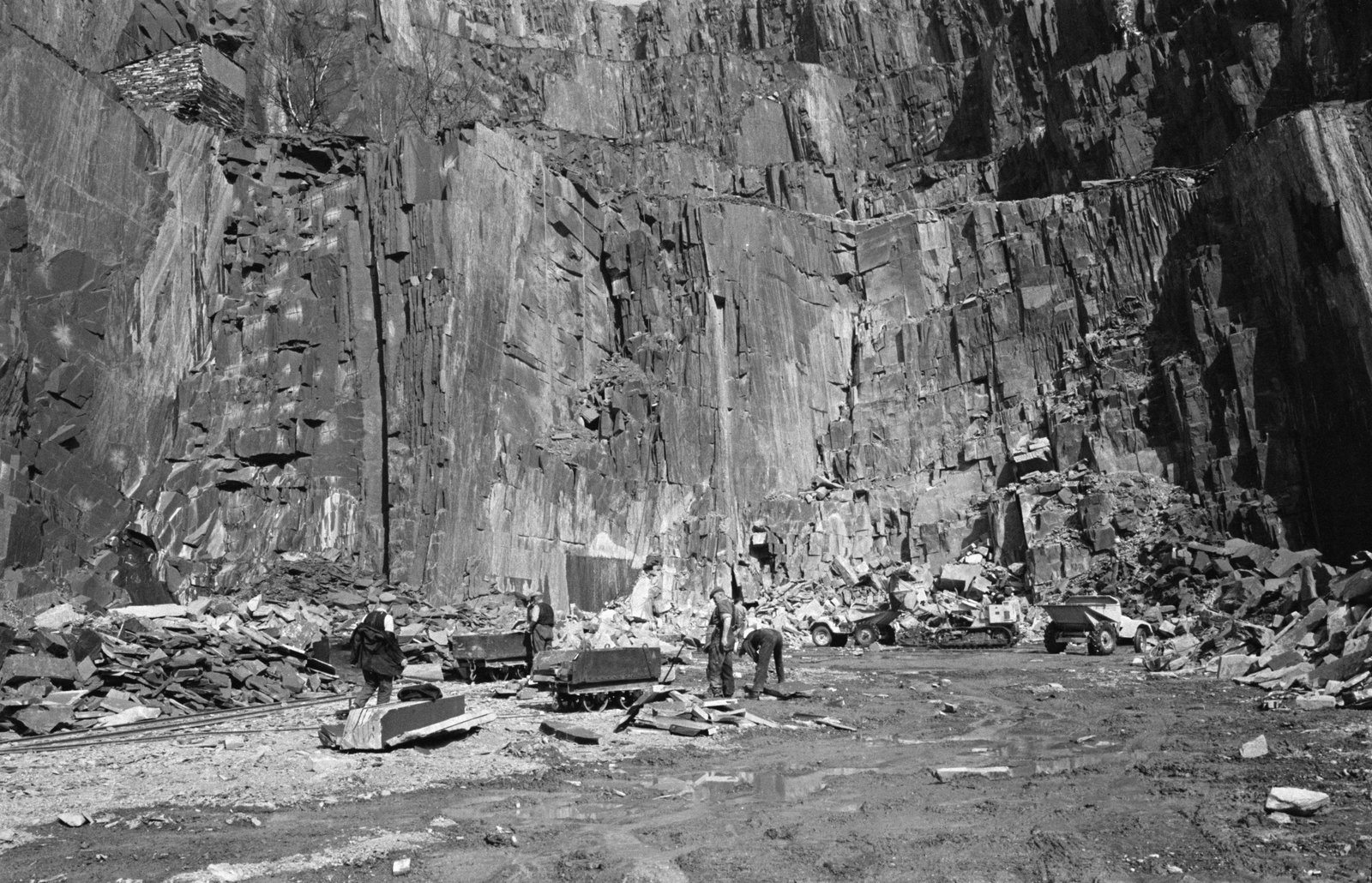

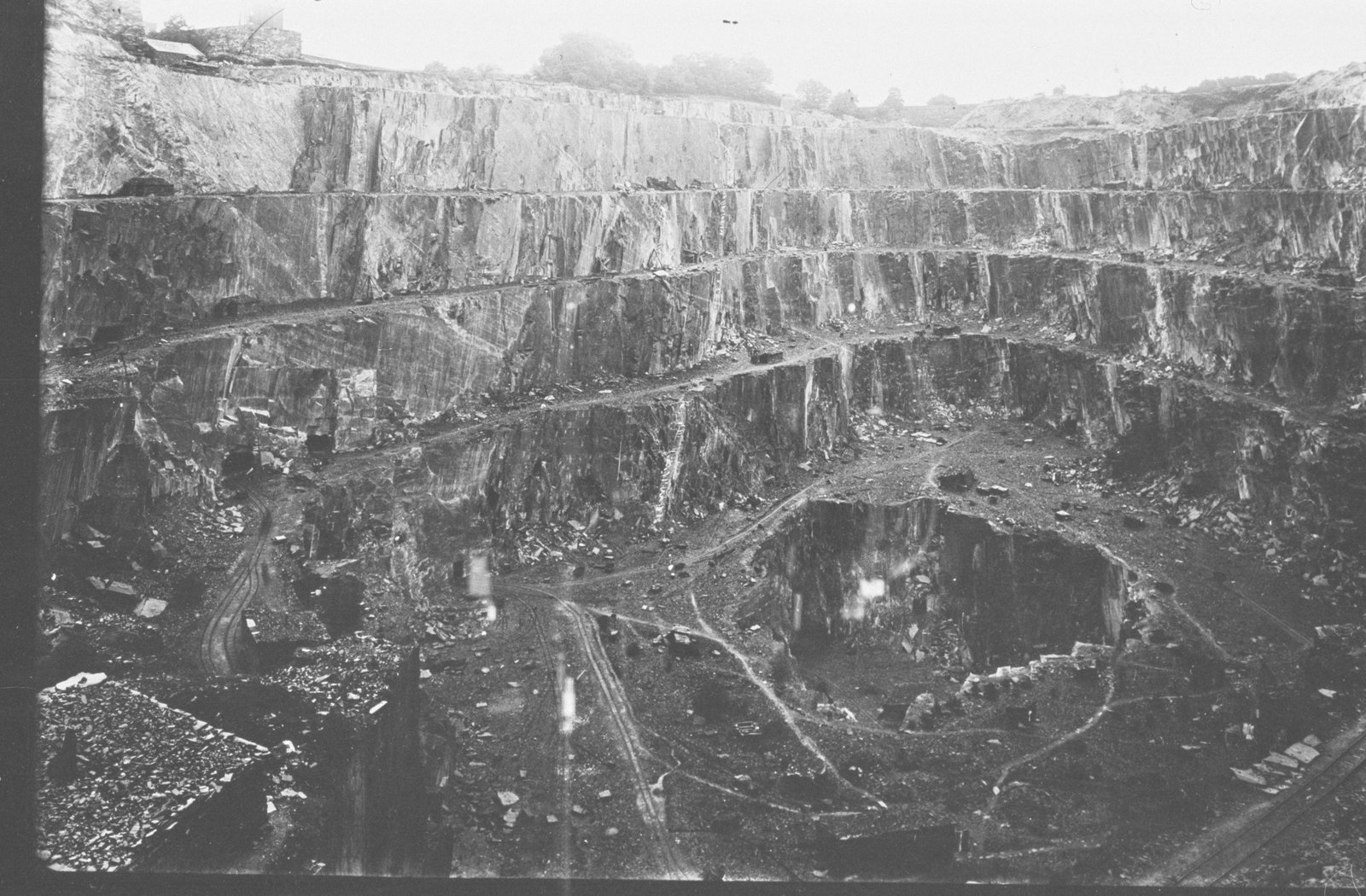

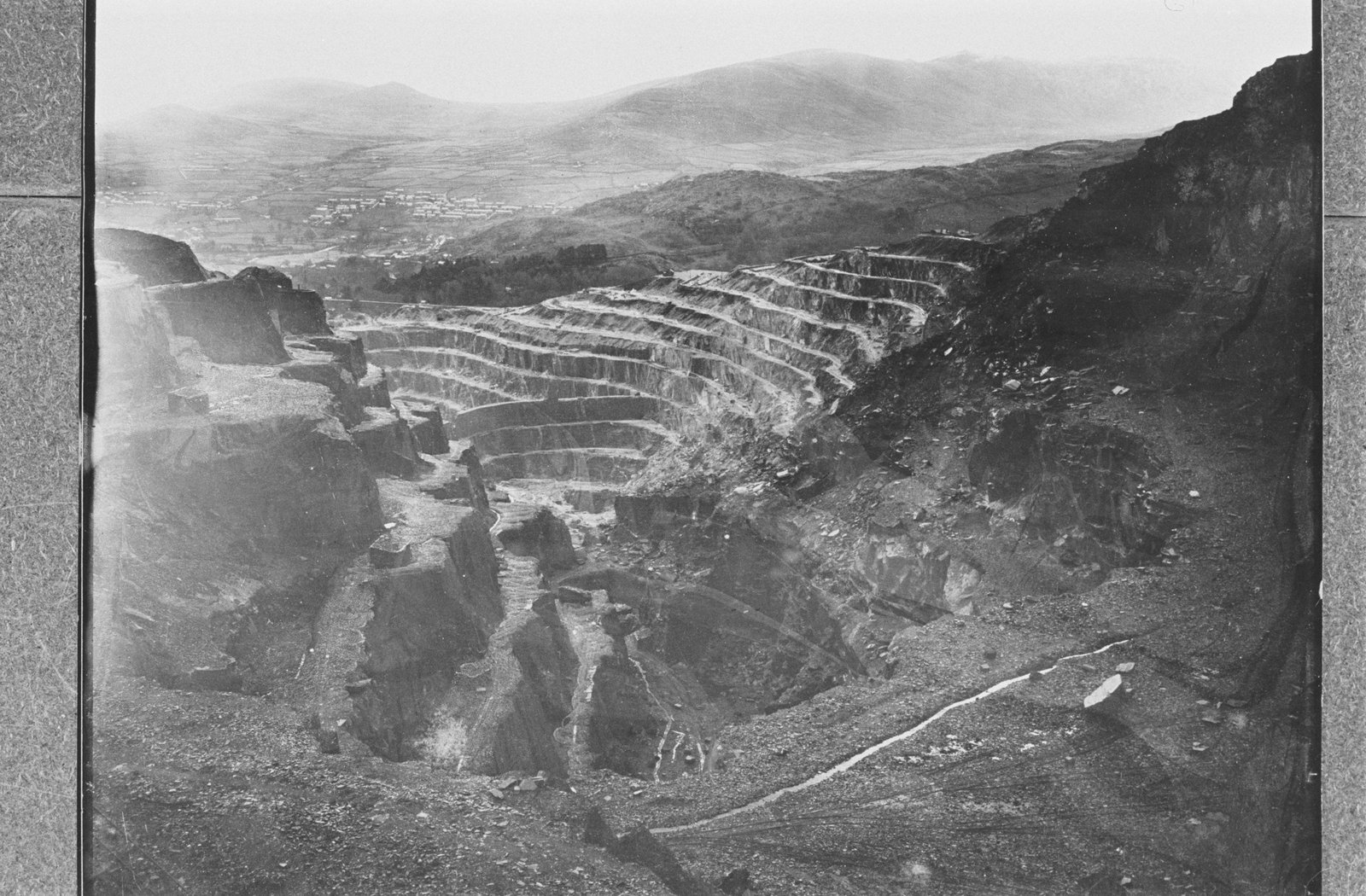

Vast quarry that dominated the North Wales Slate Industry.***

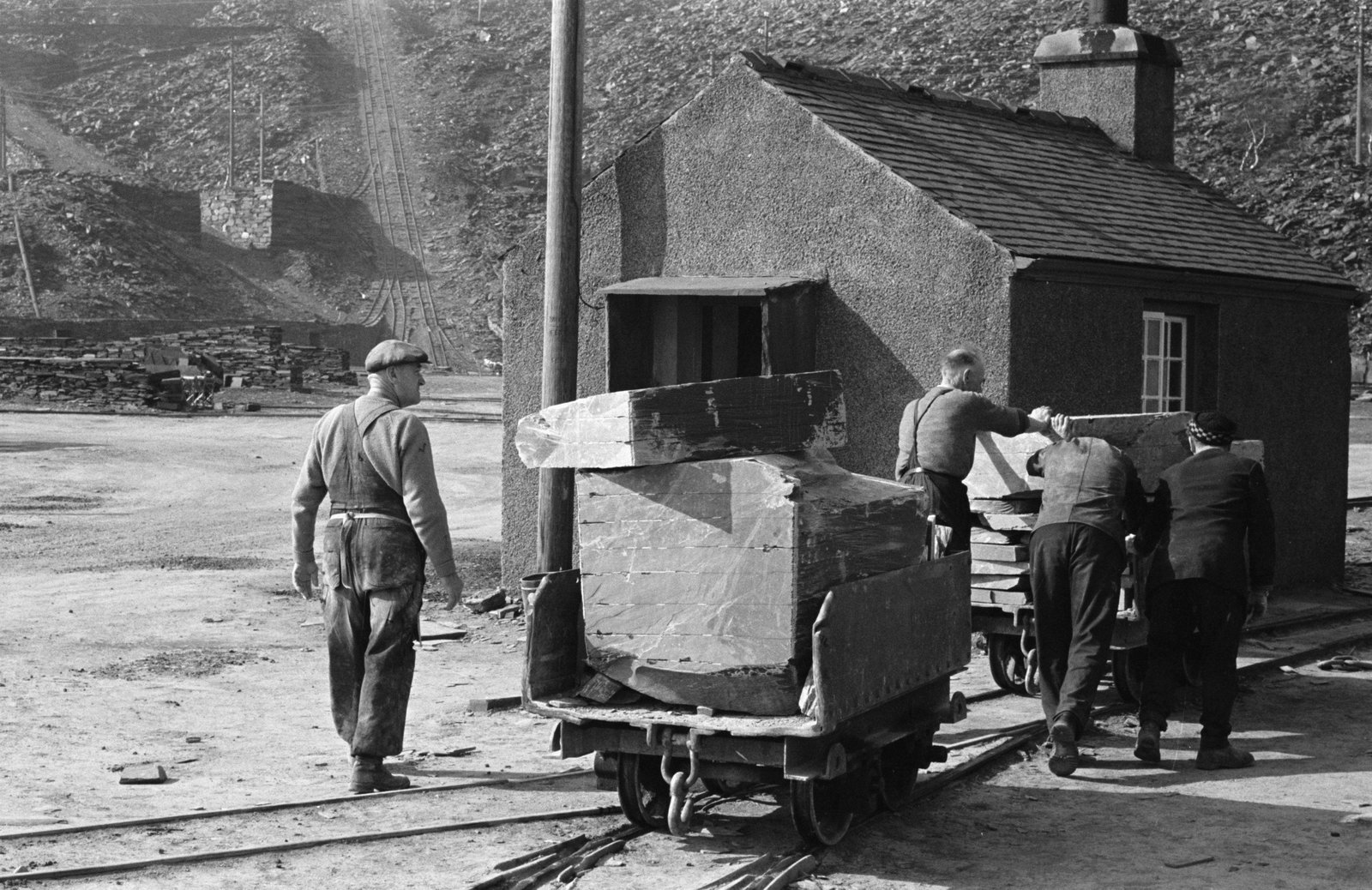

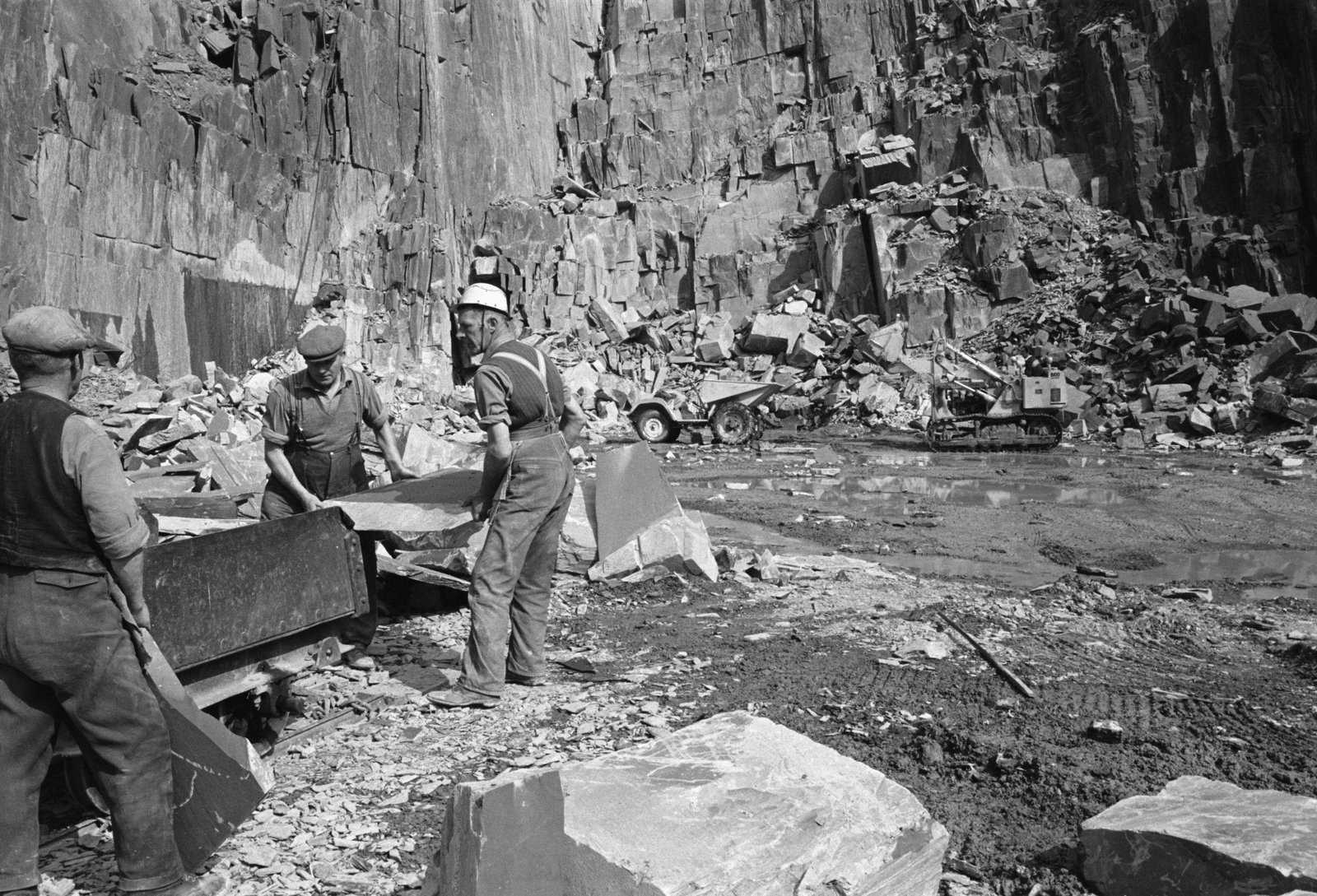

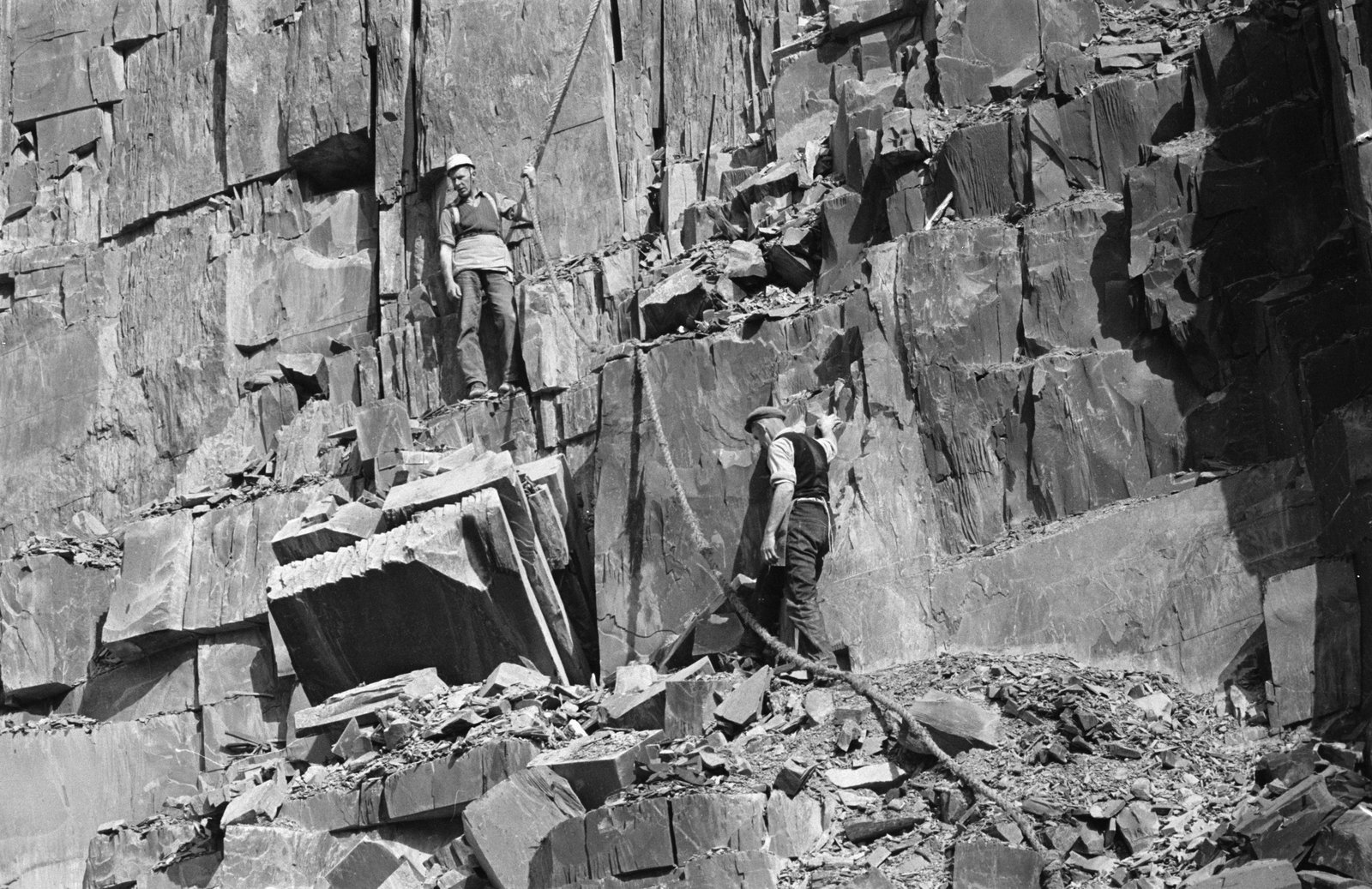

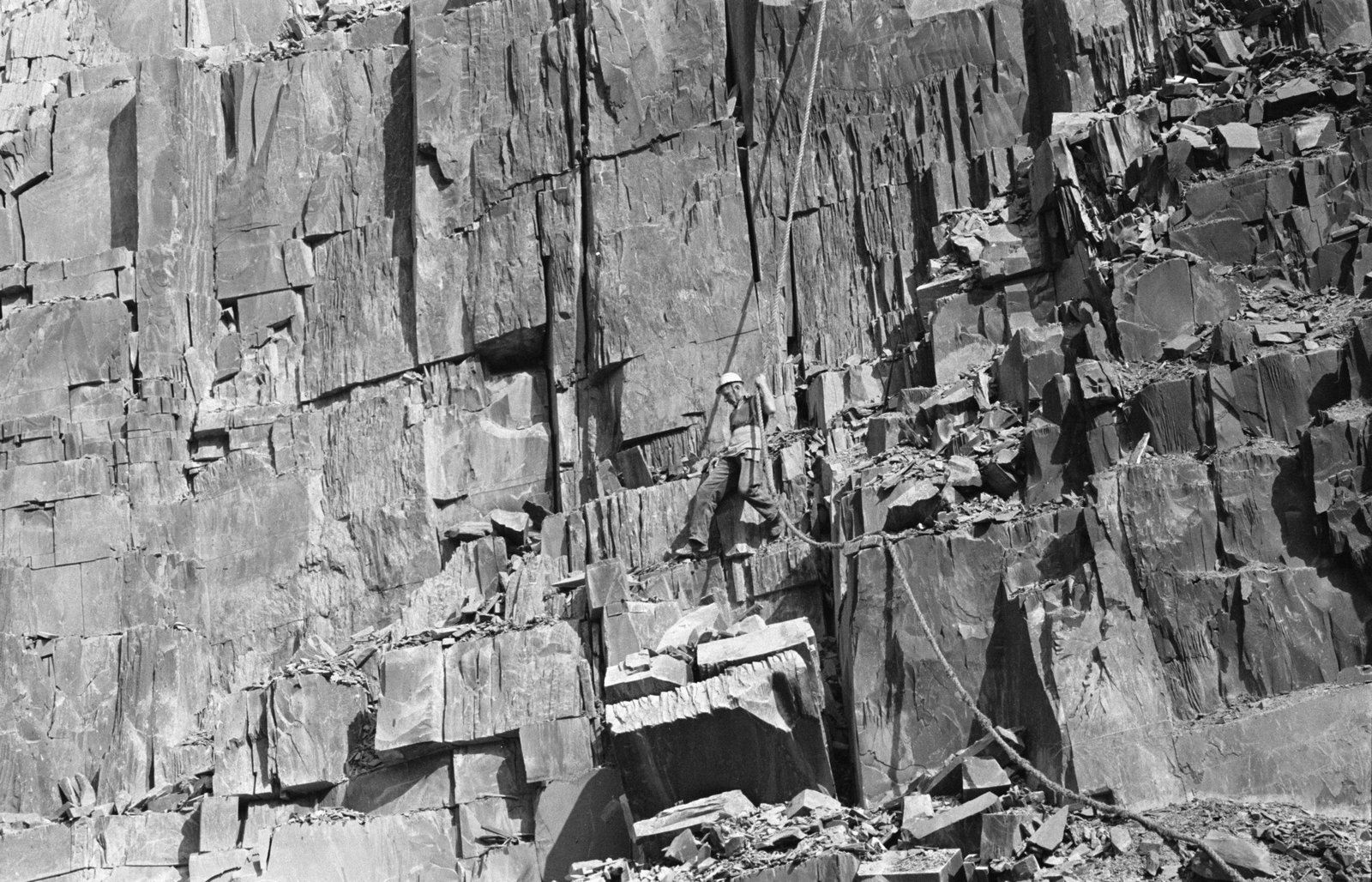

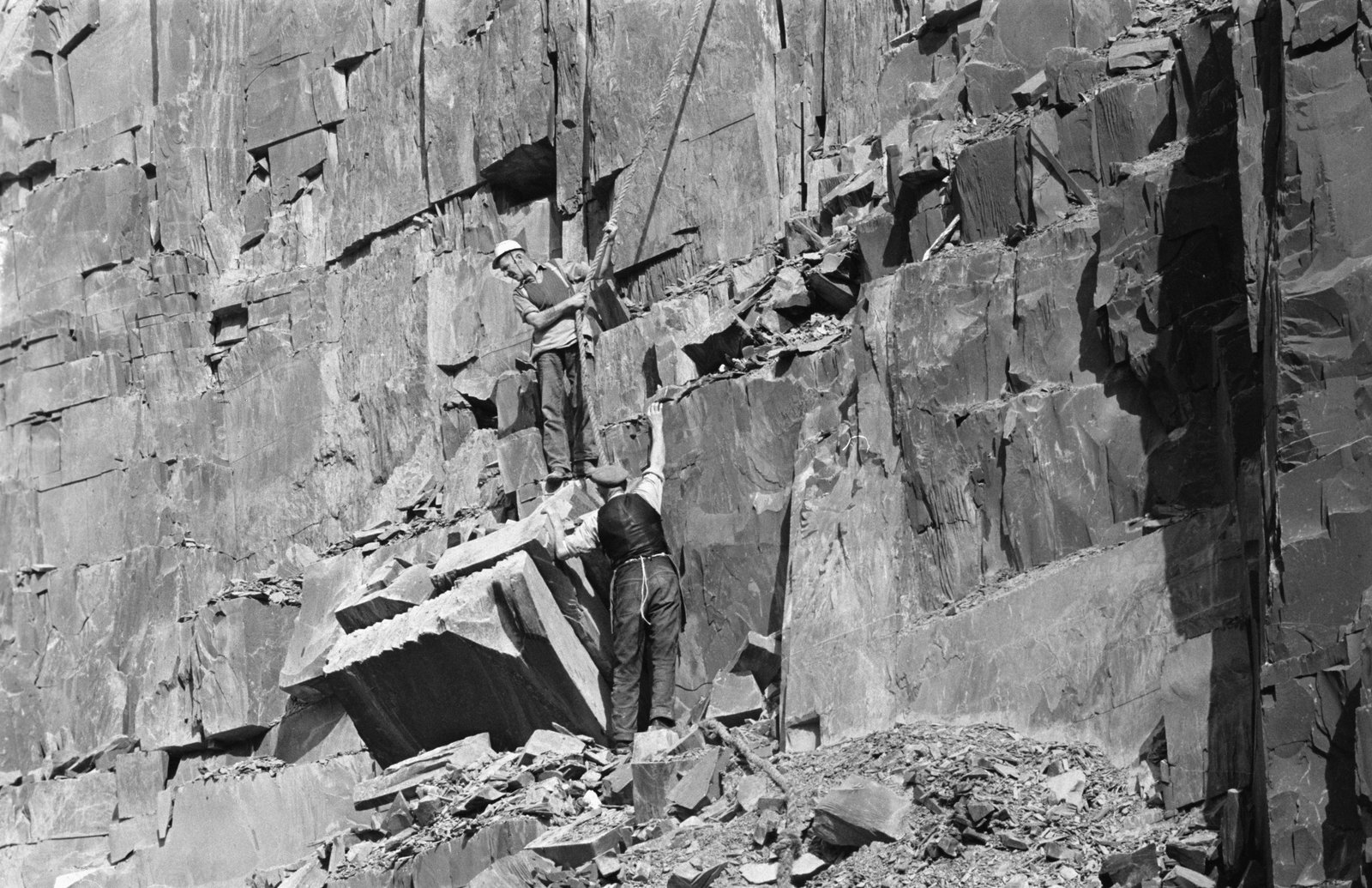

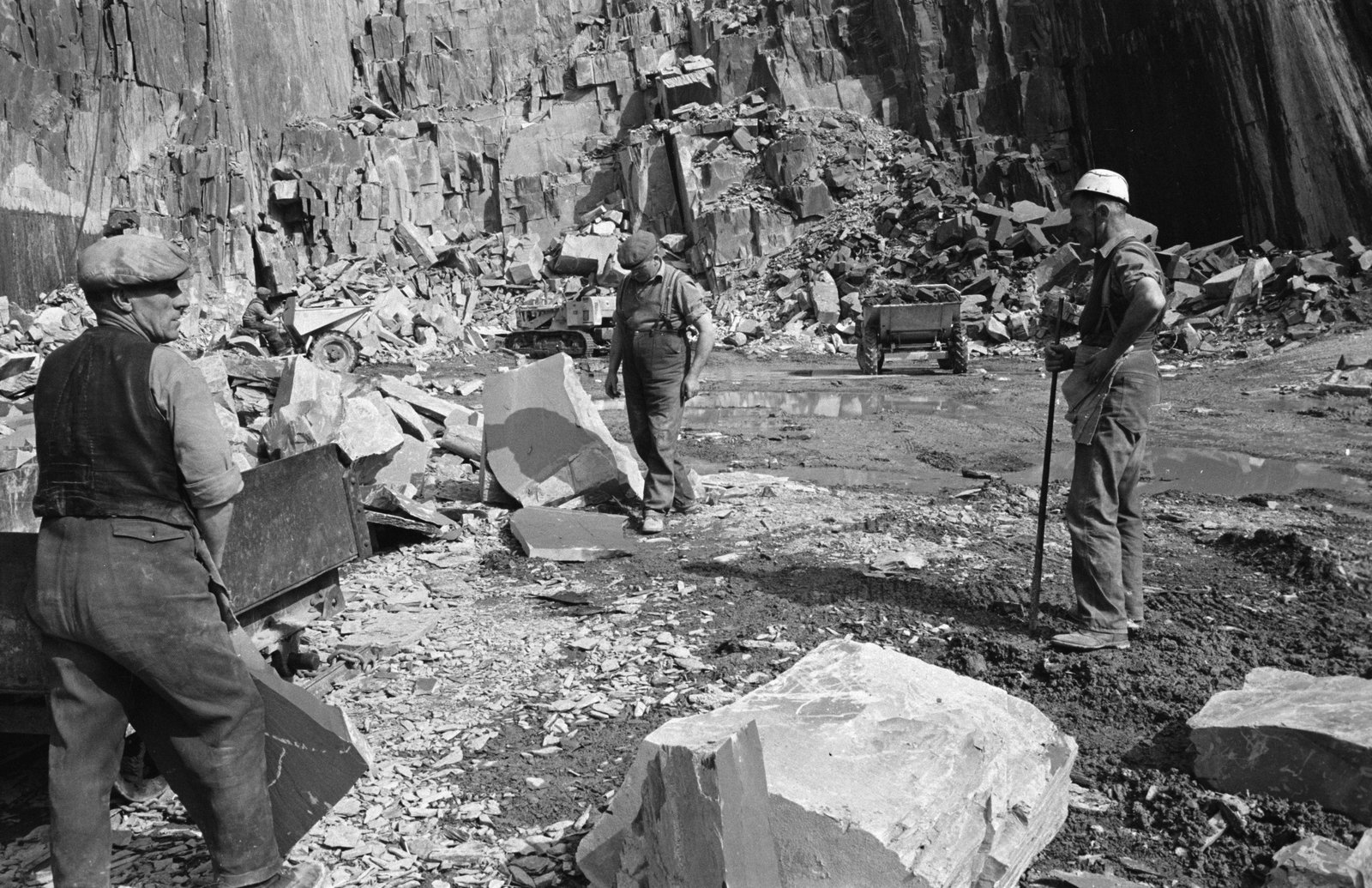

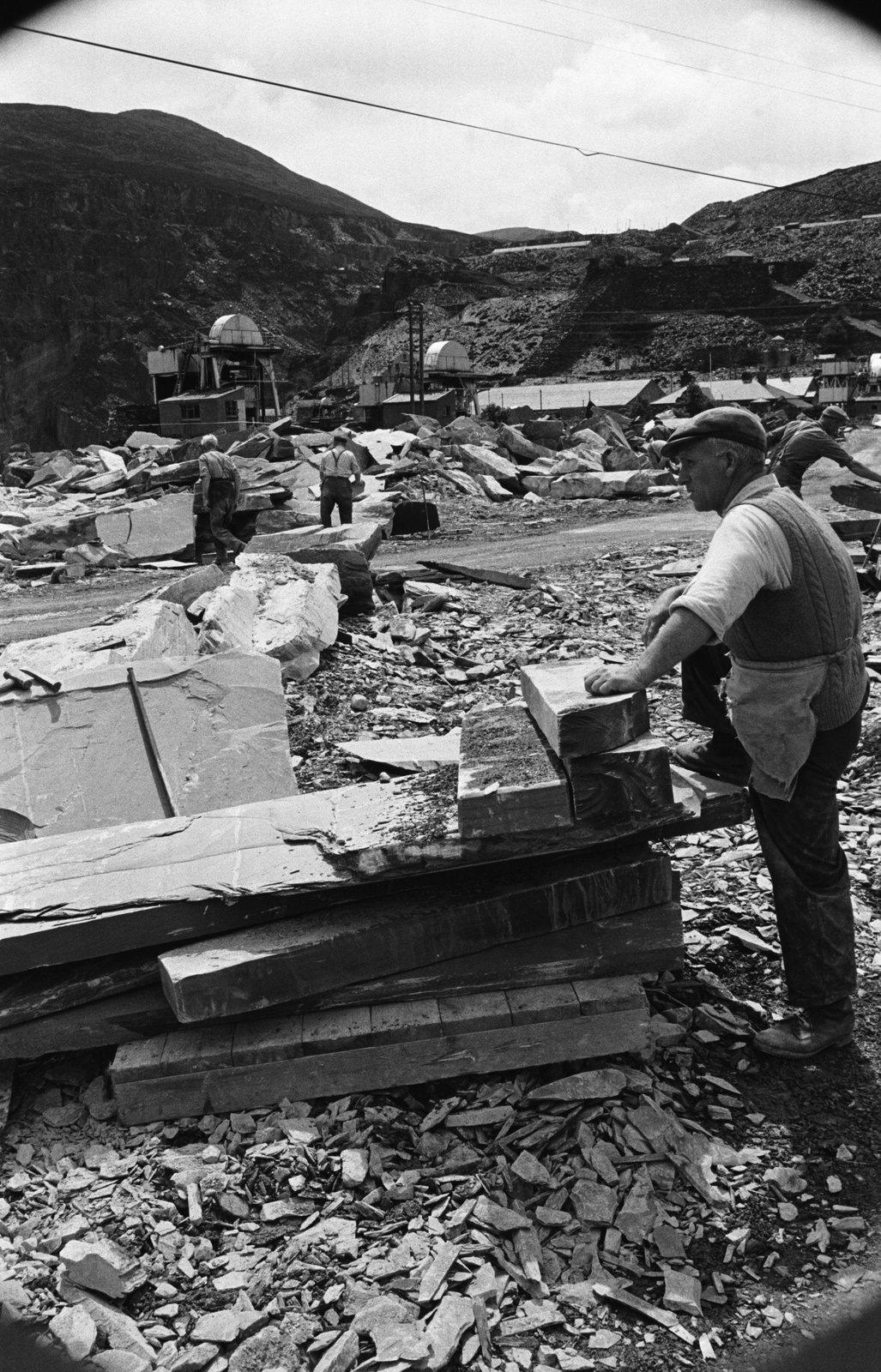

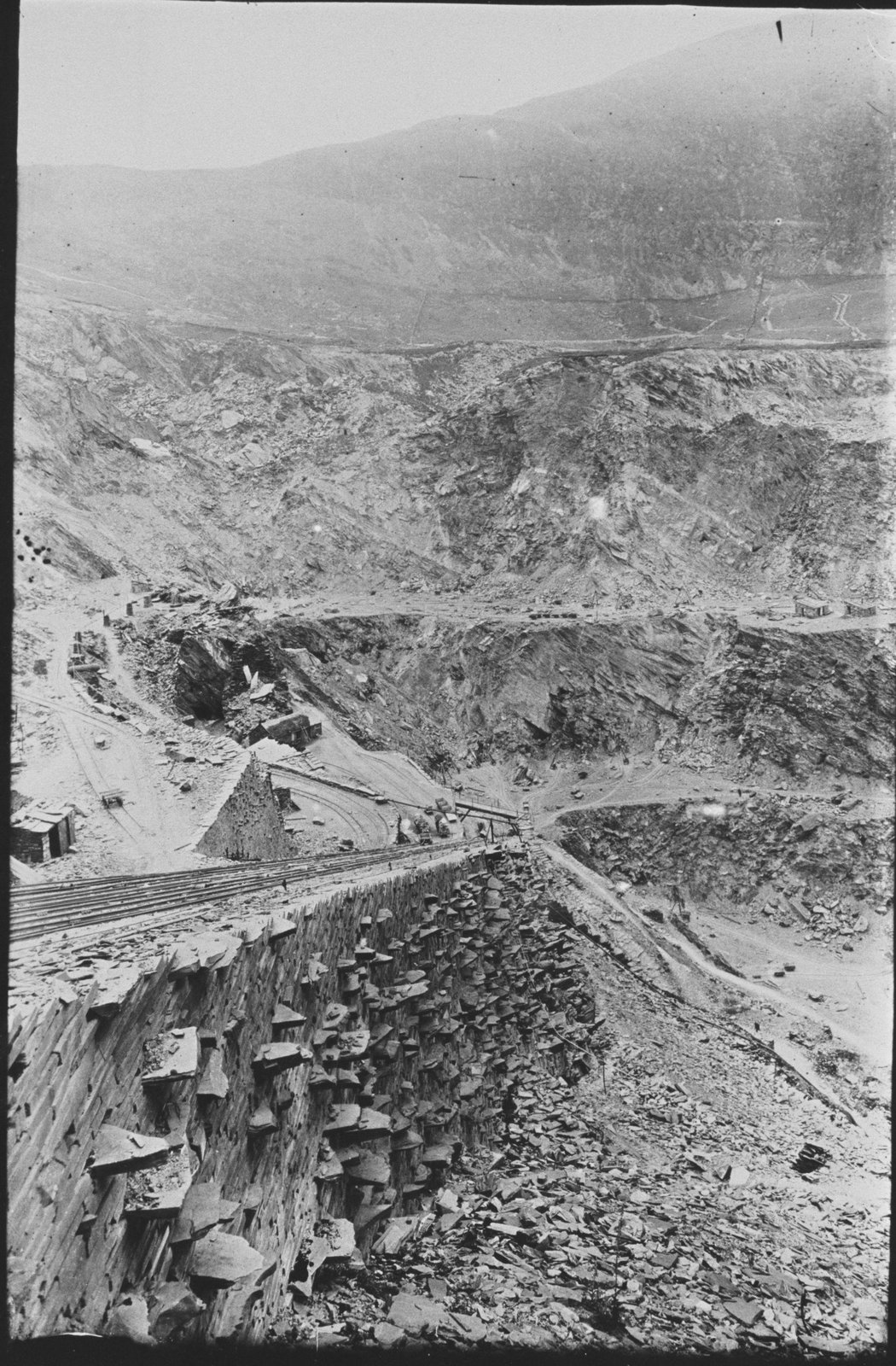

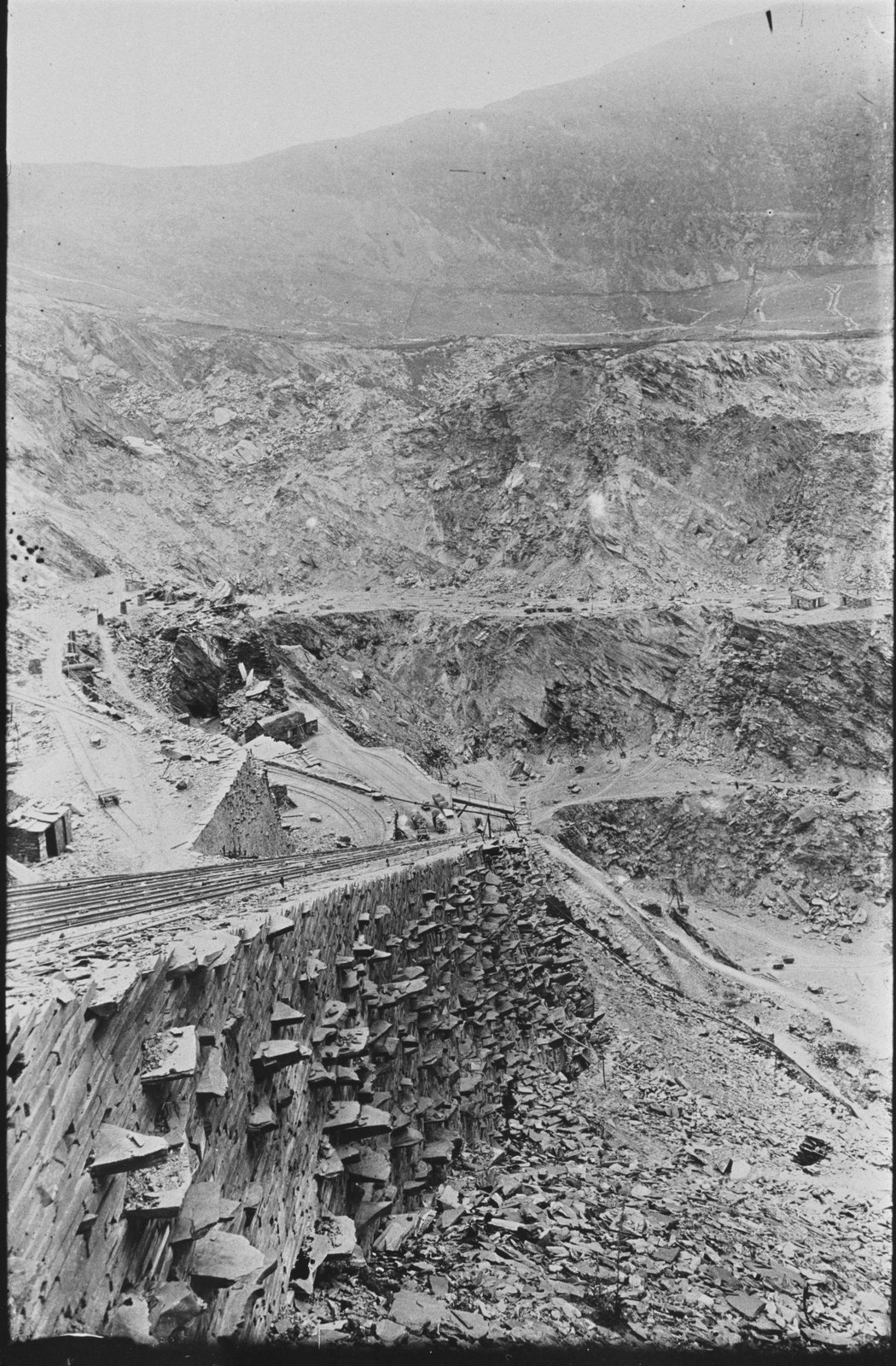

By 1798, the immense challenge of enabling a large number of men to work simultaneously was resolved by implementing the gallery system. This terraced the working face into 21 levels, with each gallery separated by a height of 65 to 70 feet and possessing its own rail system.

Movement downwards was primarily handled by self-acting inclines. That upwards was facilitated by unique water balance lifts. Later, some use was made of Blondin aerial ropeways for material transport.

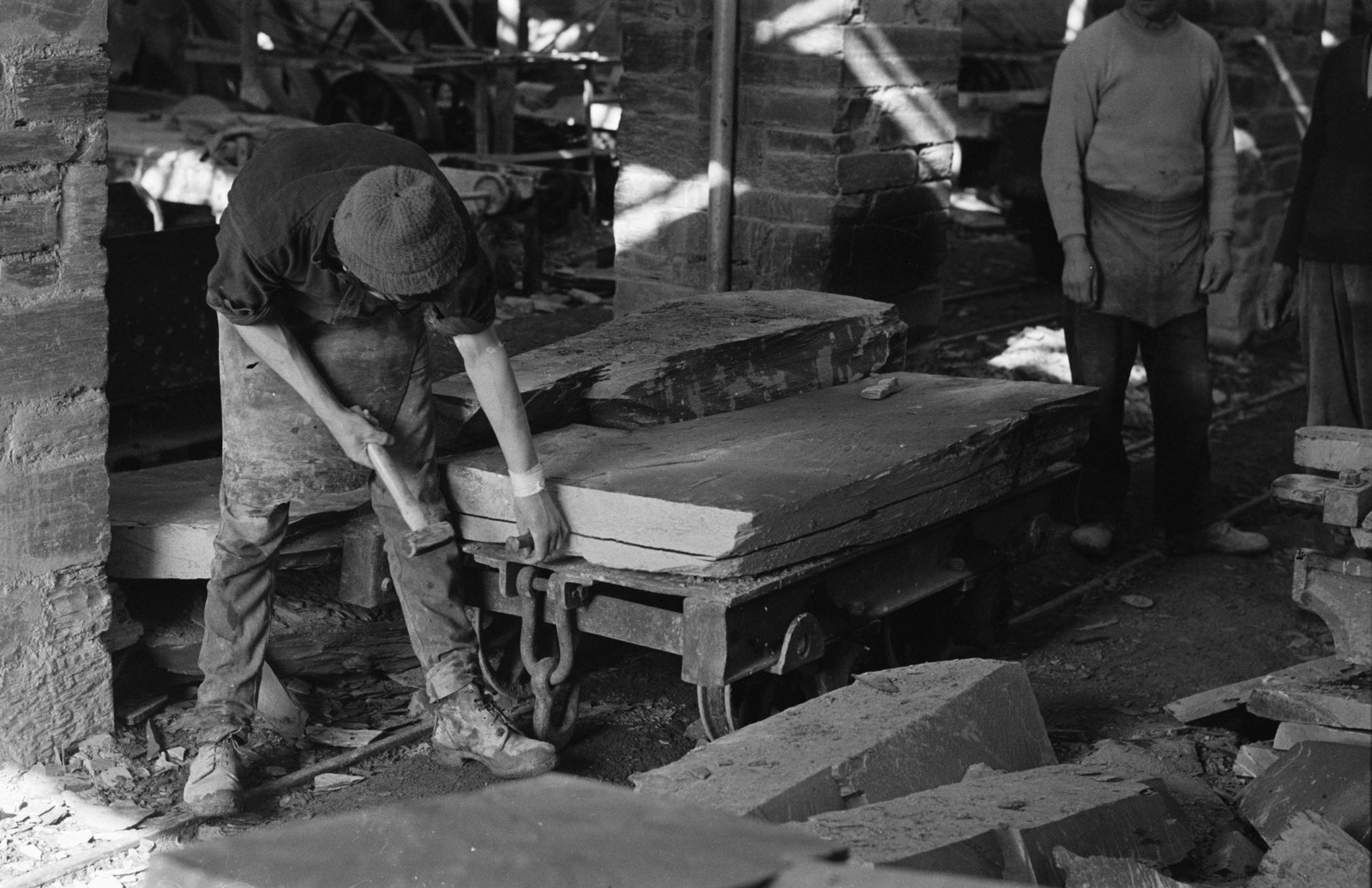

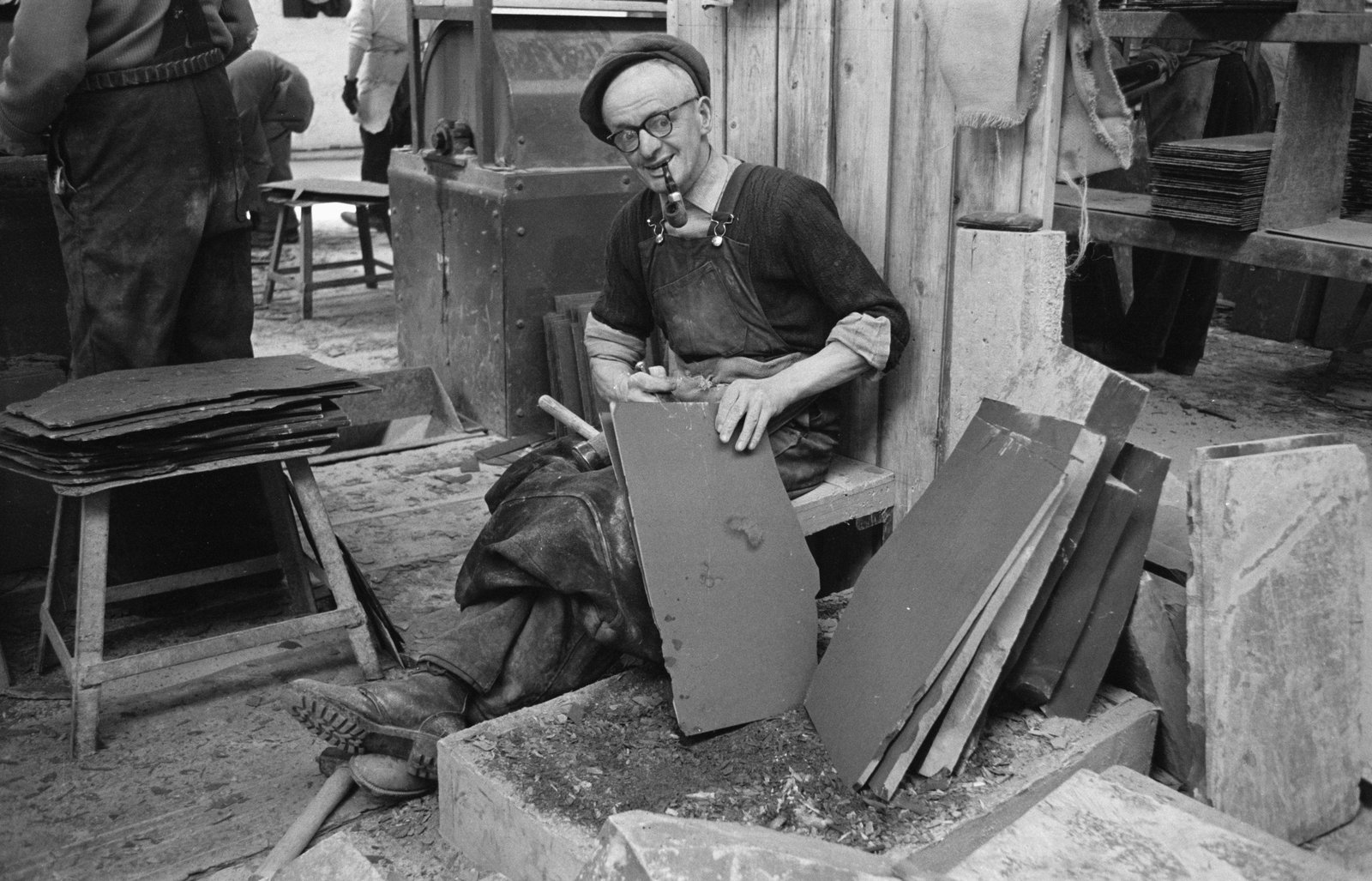

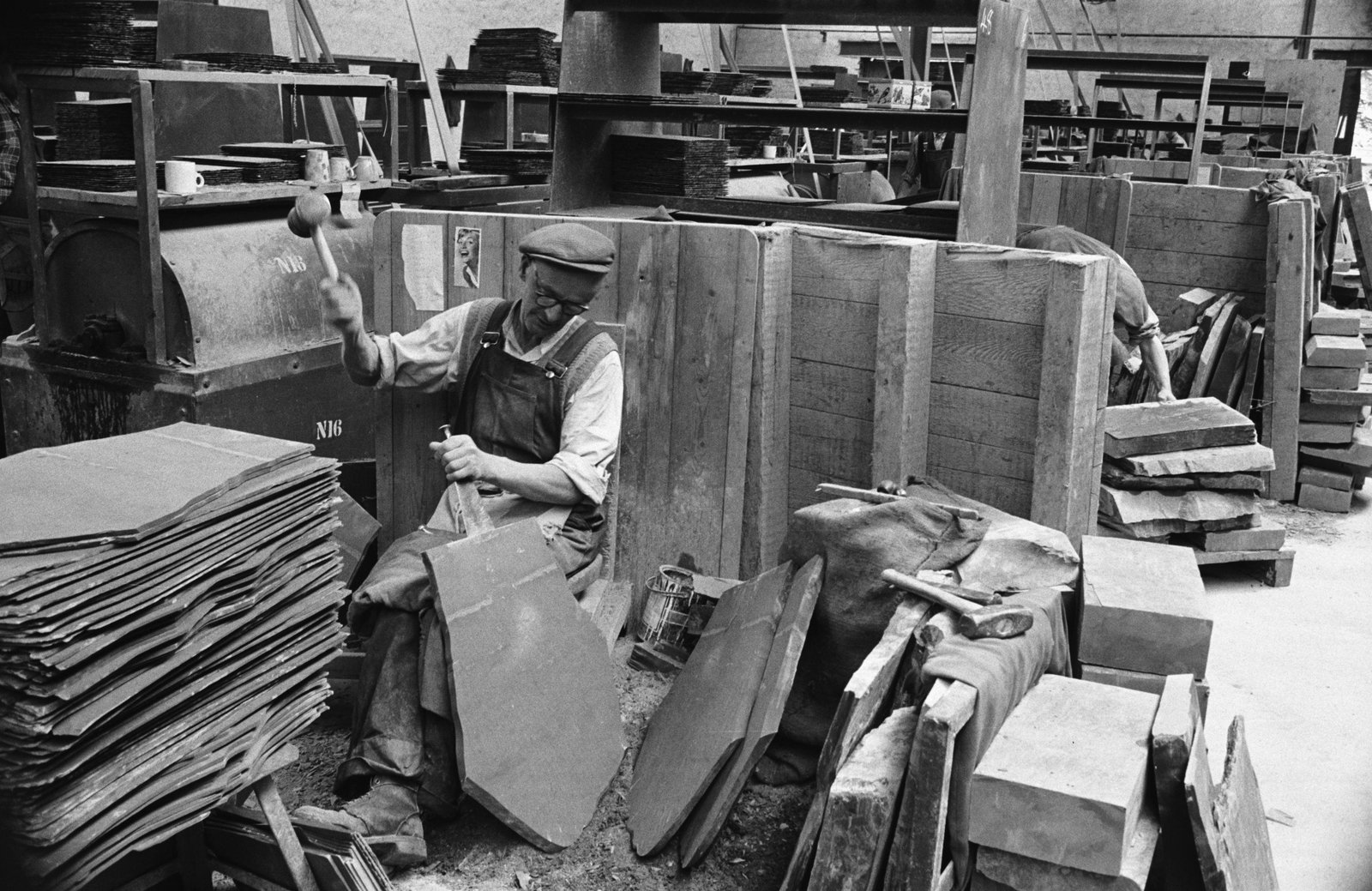

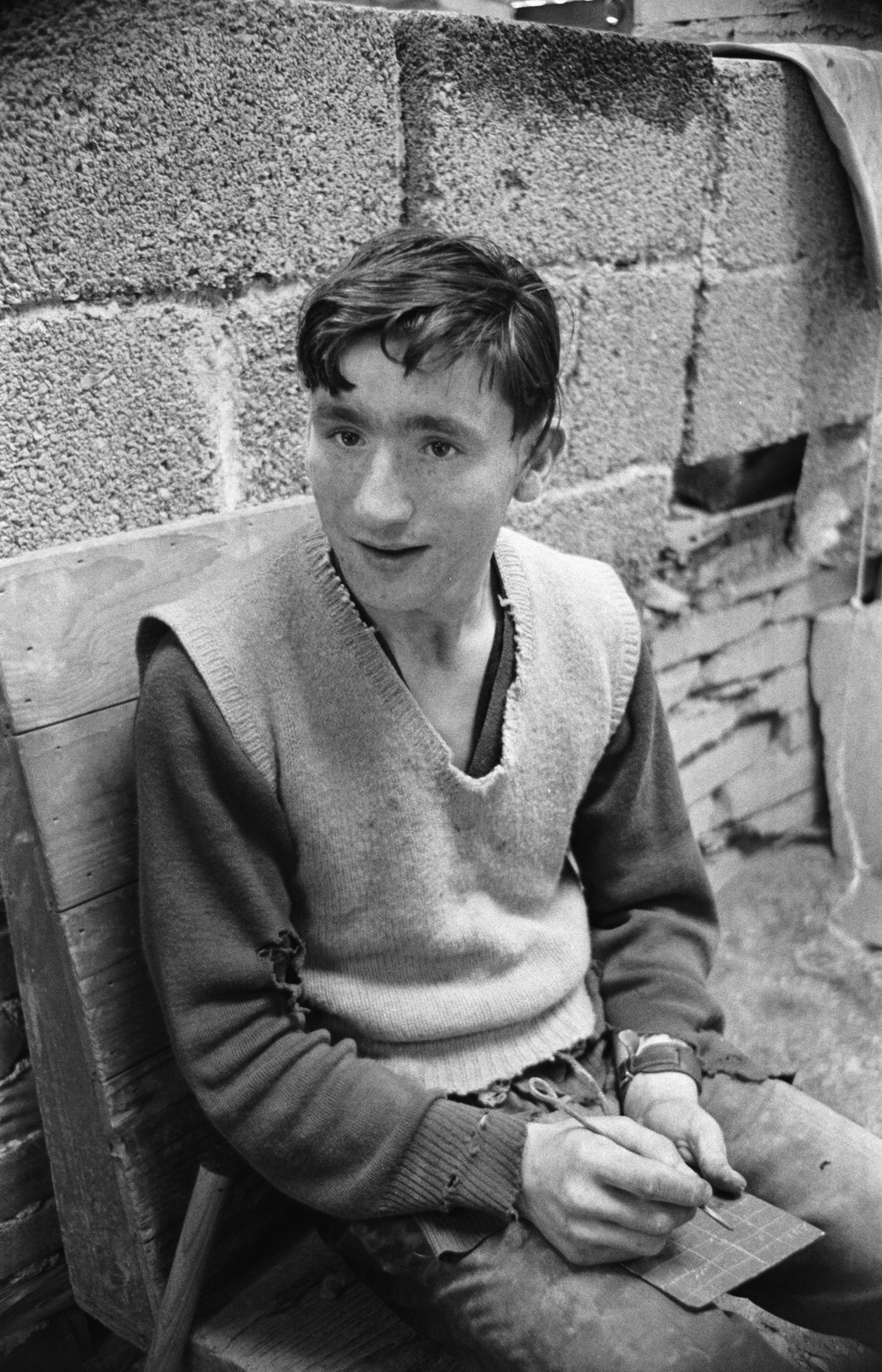

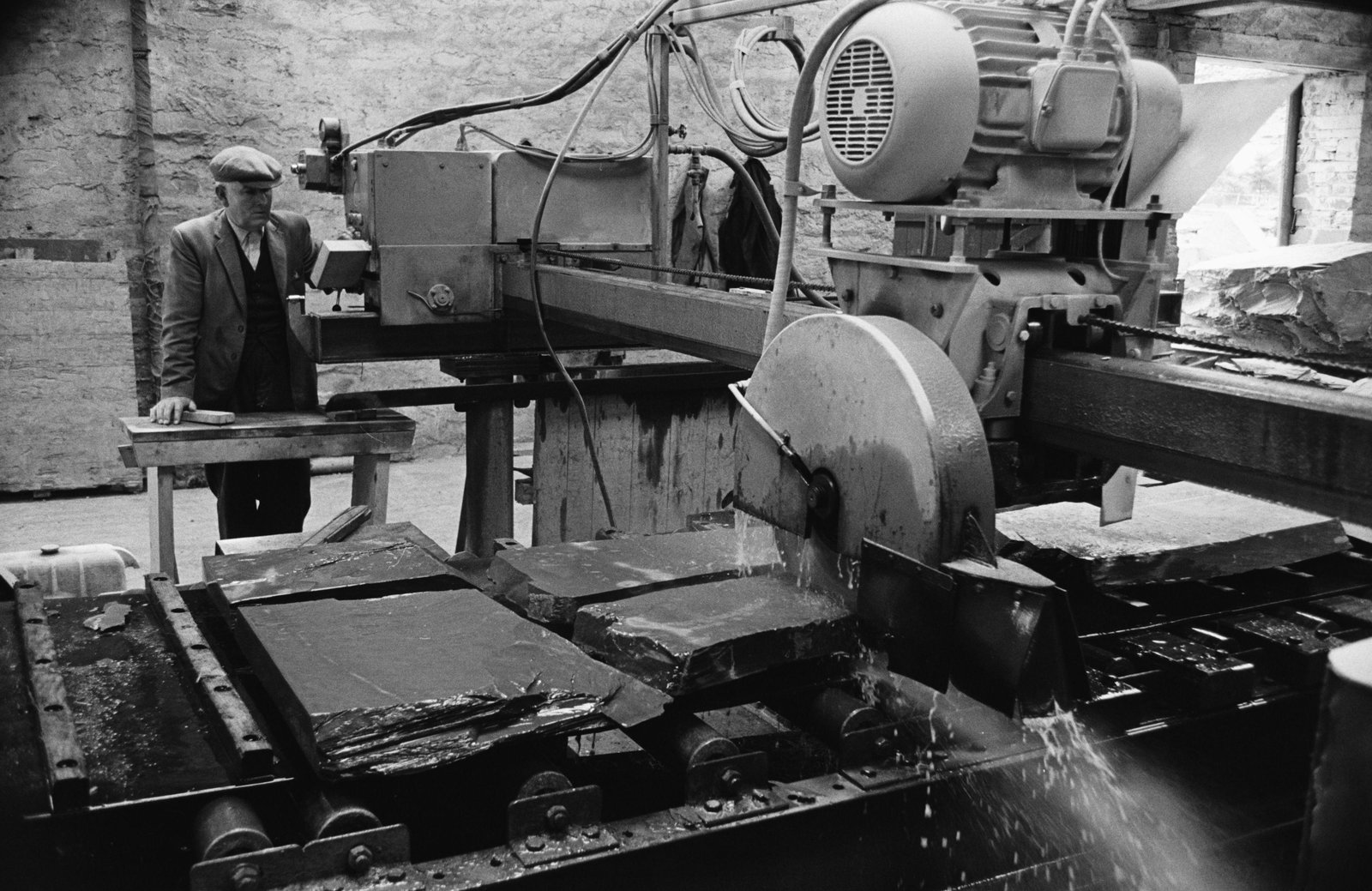

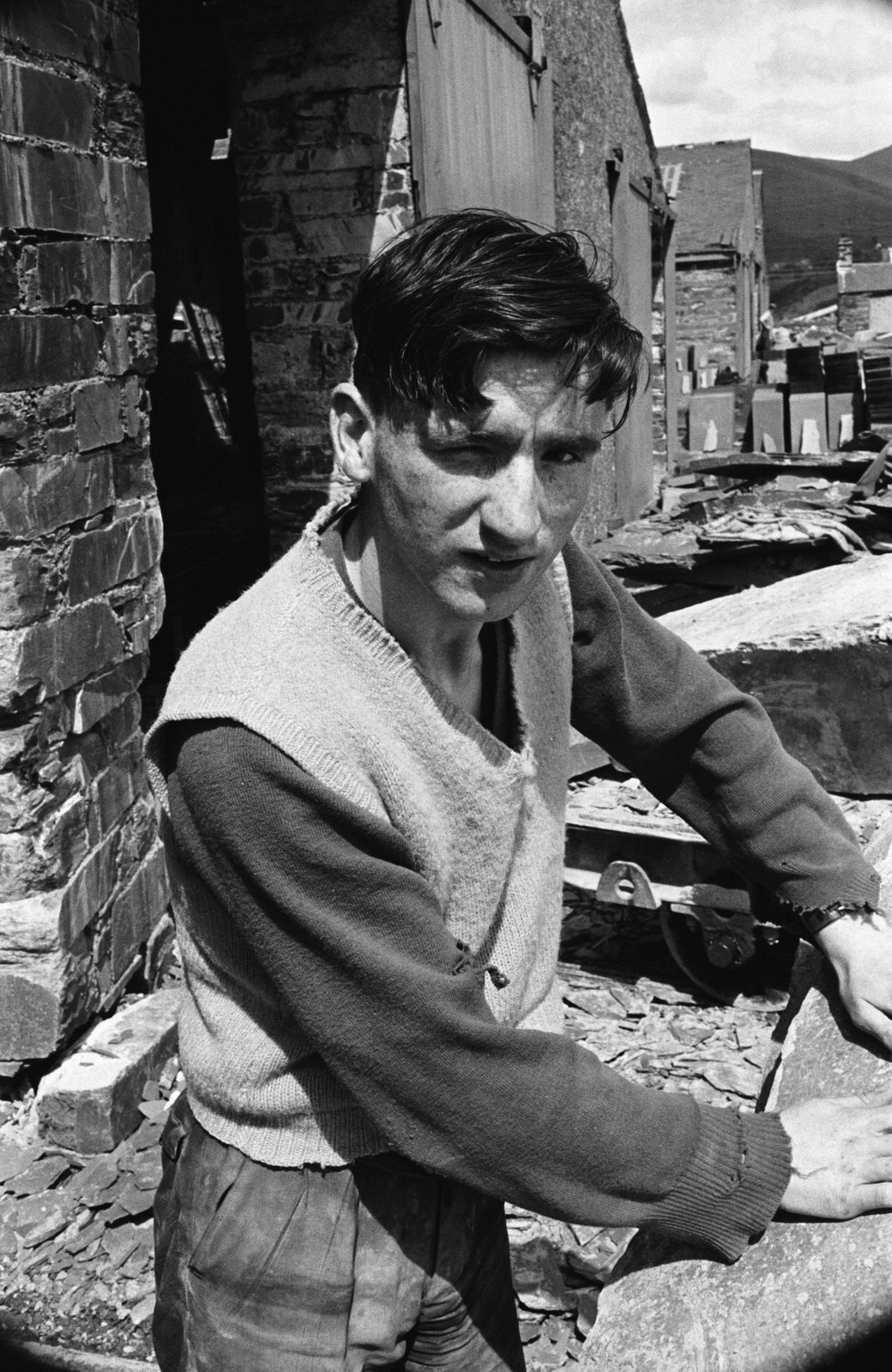

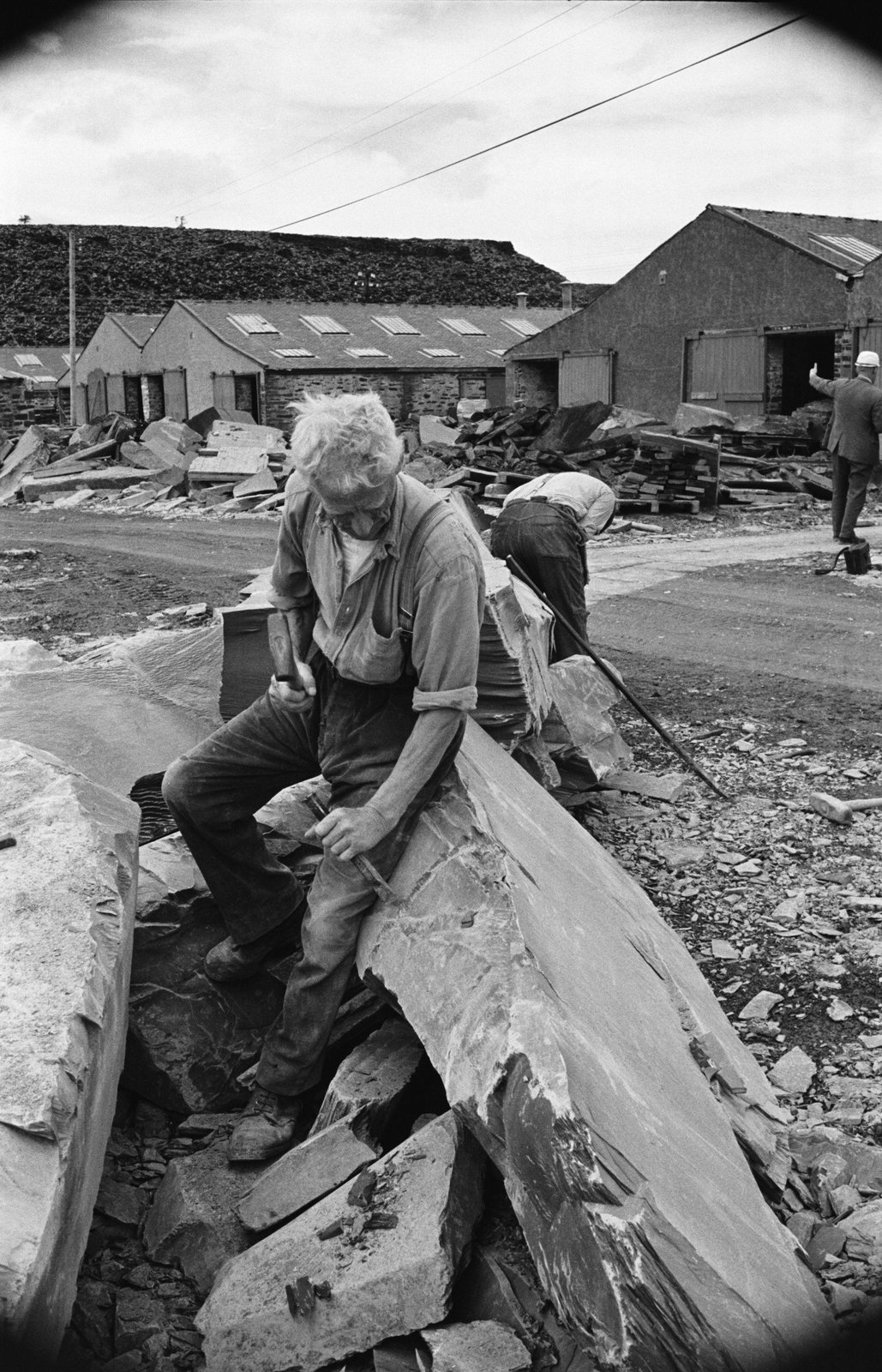

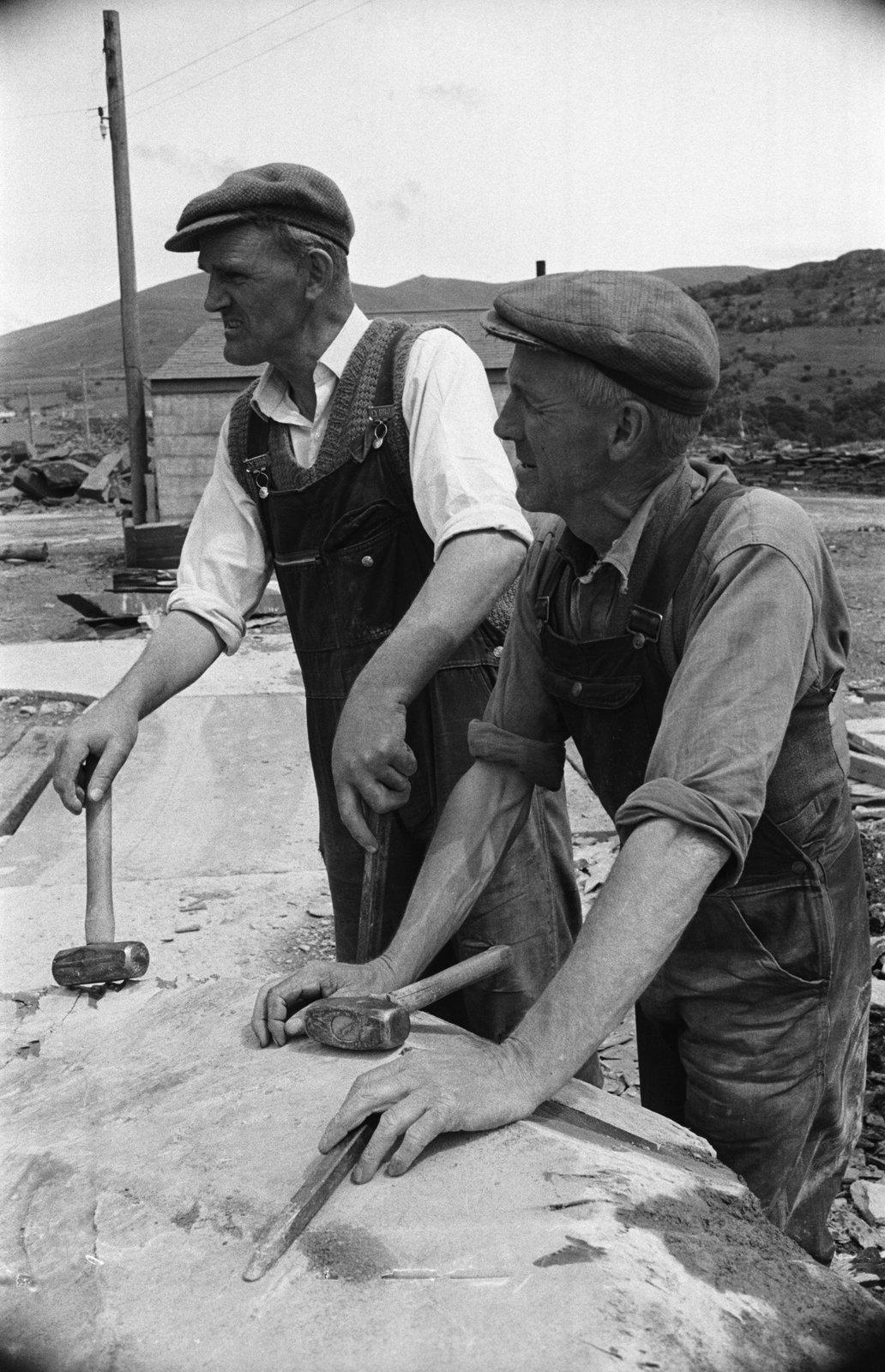

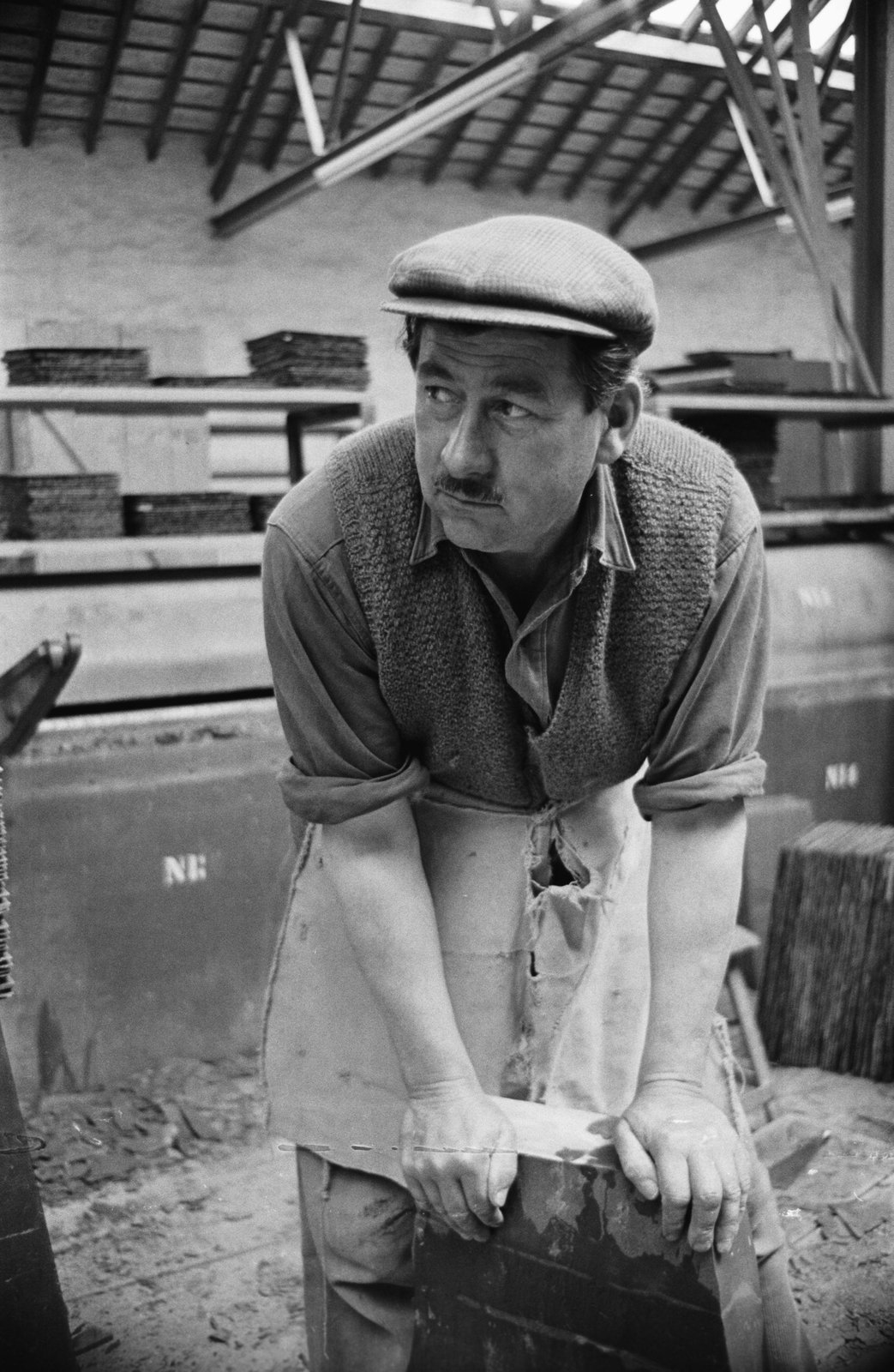

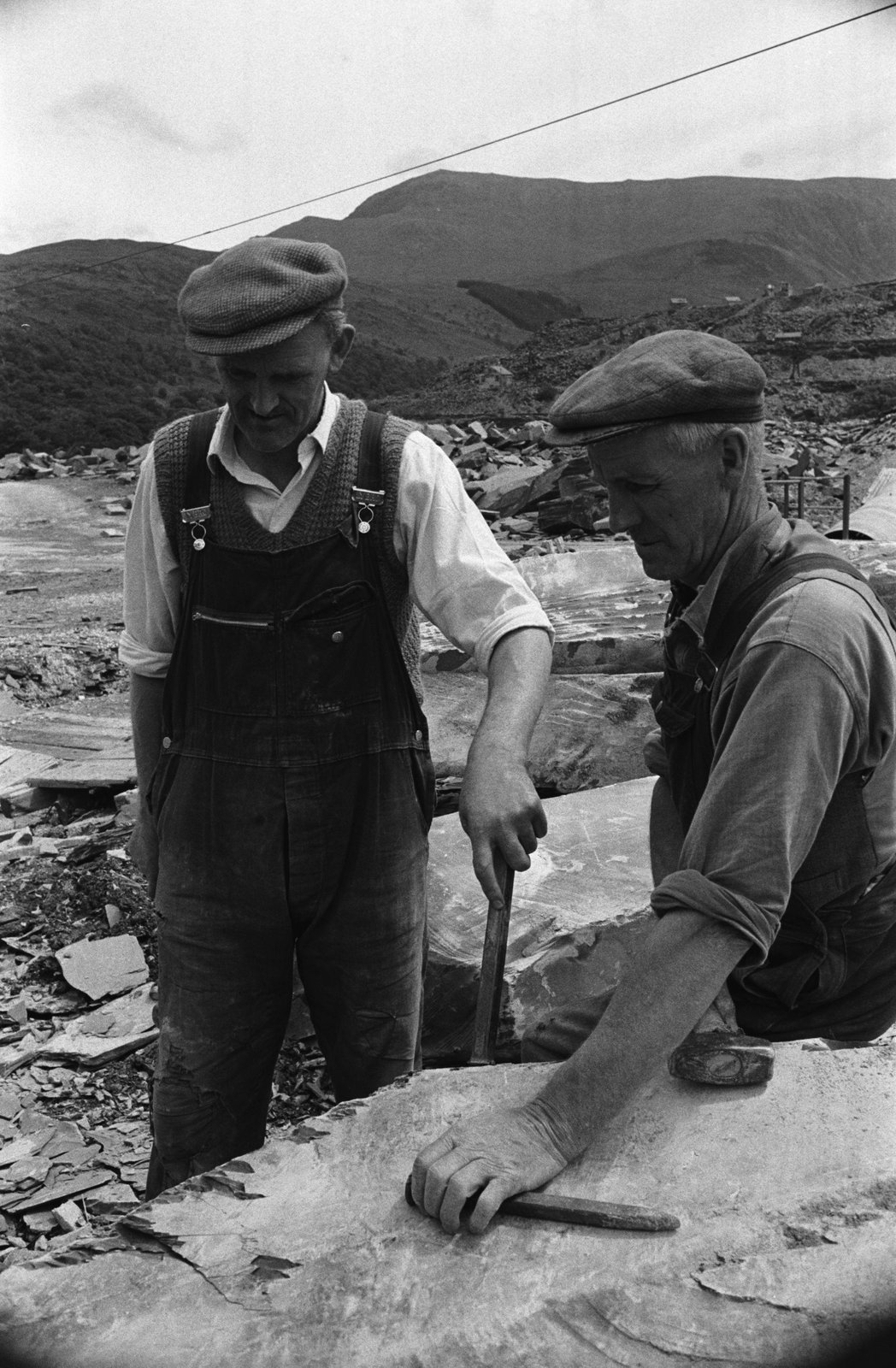

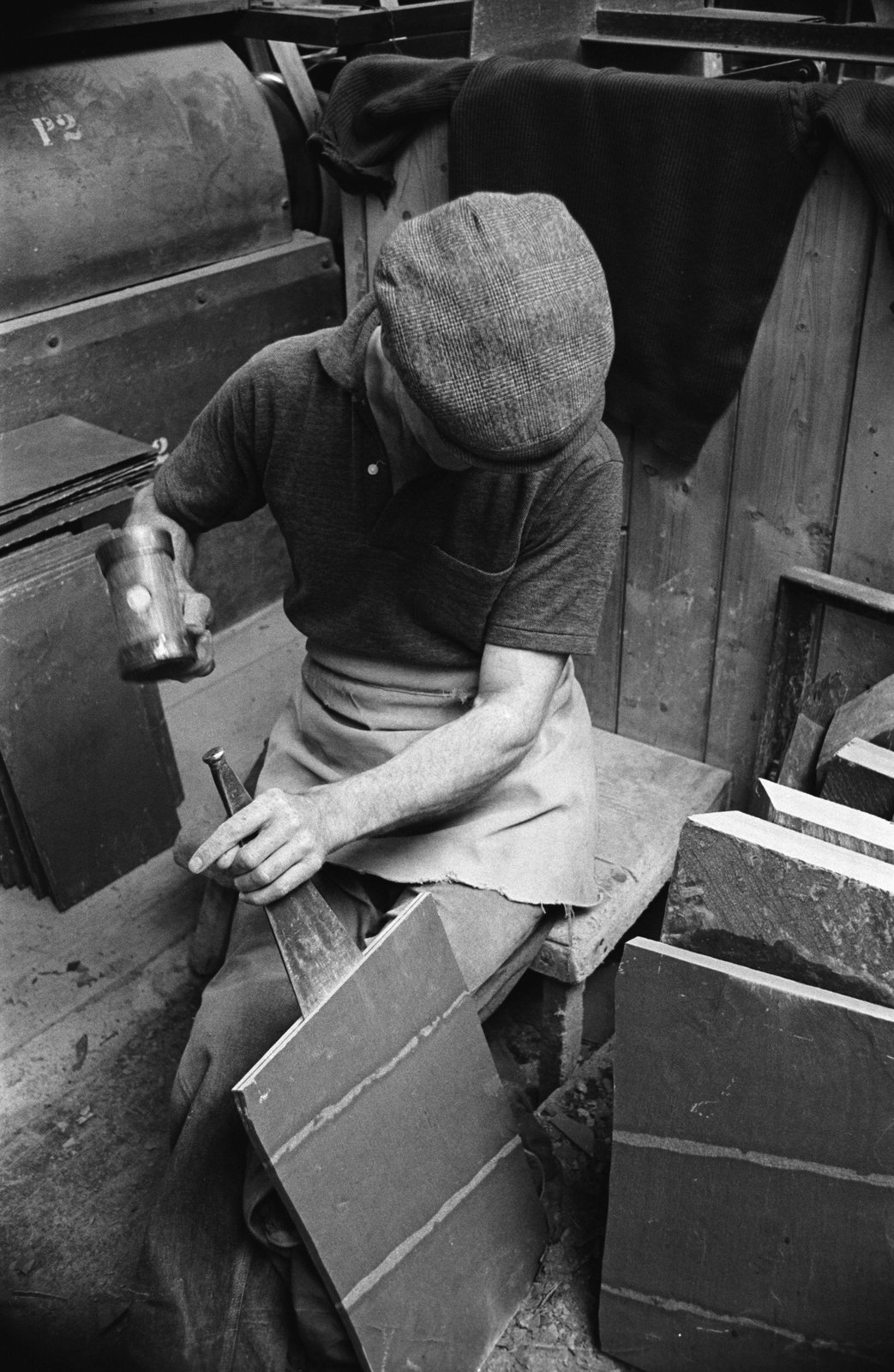

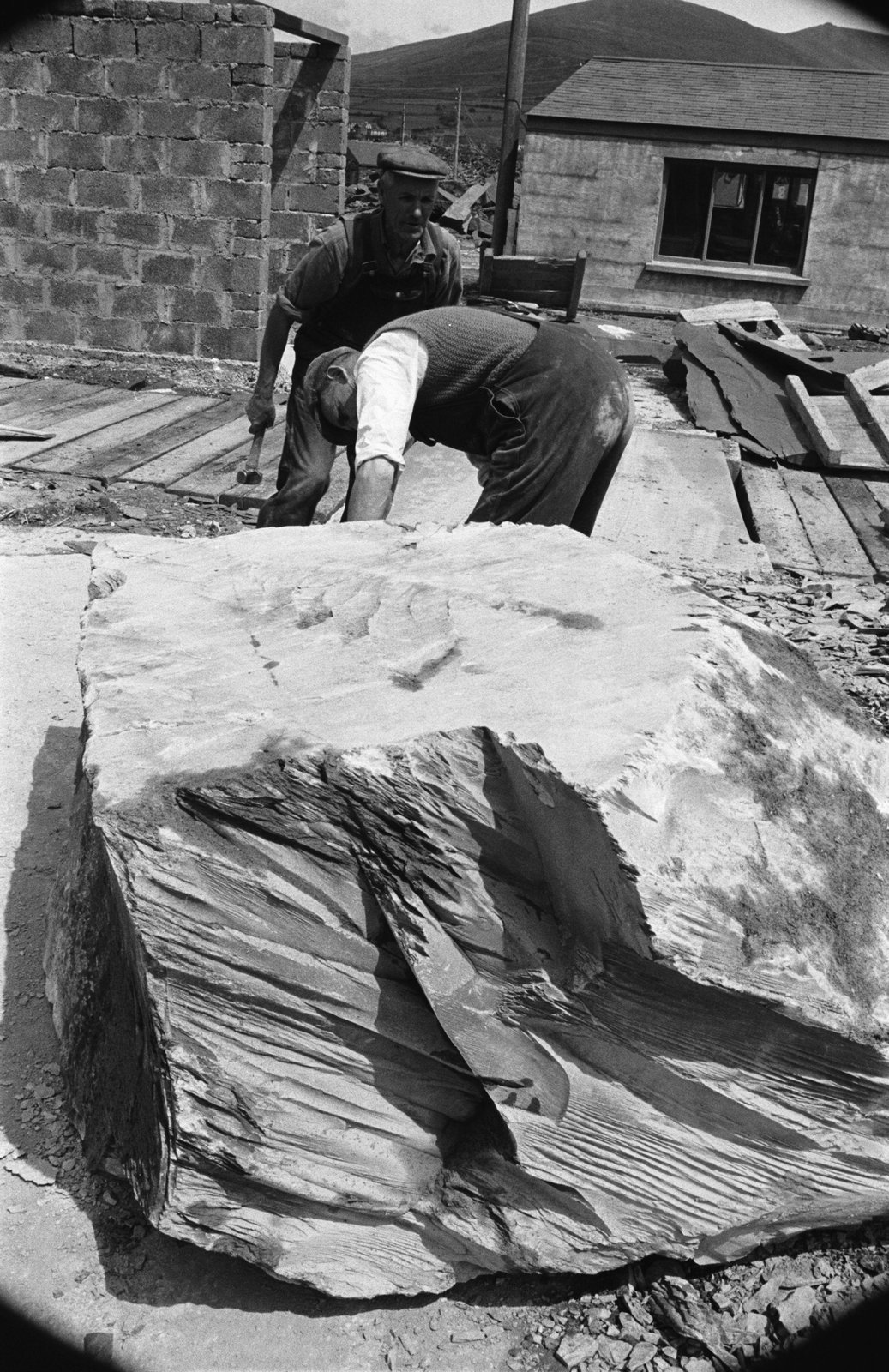

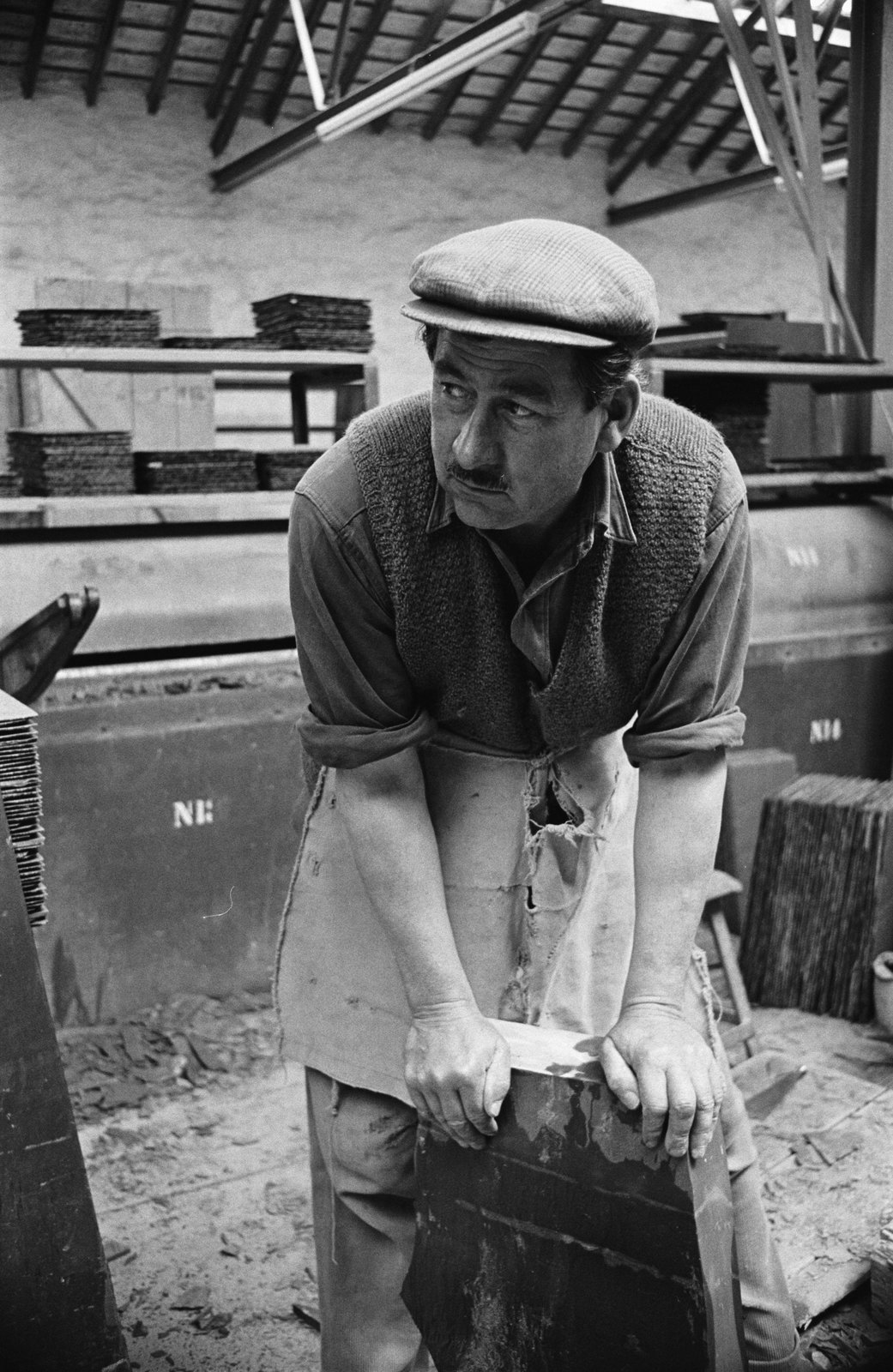

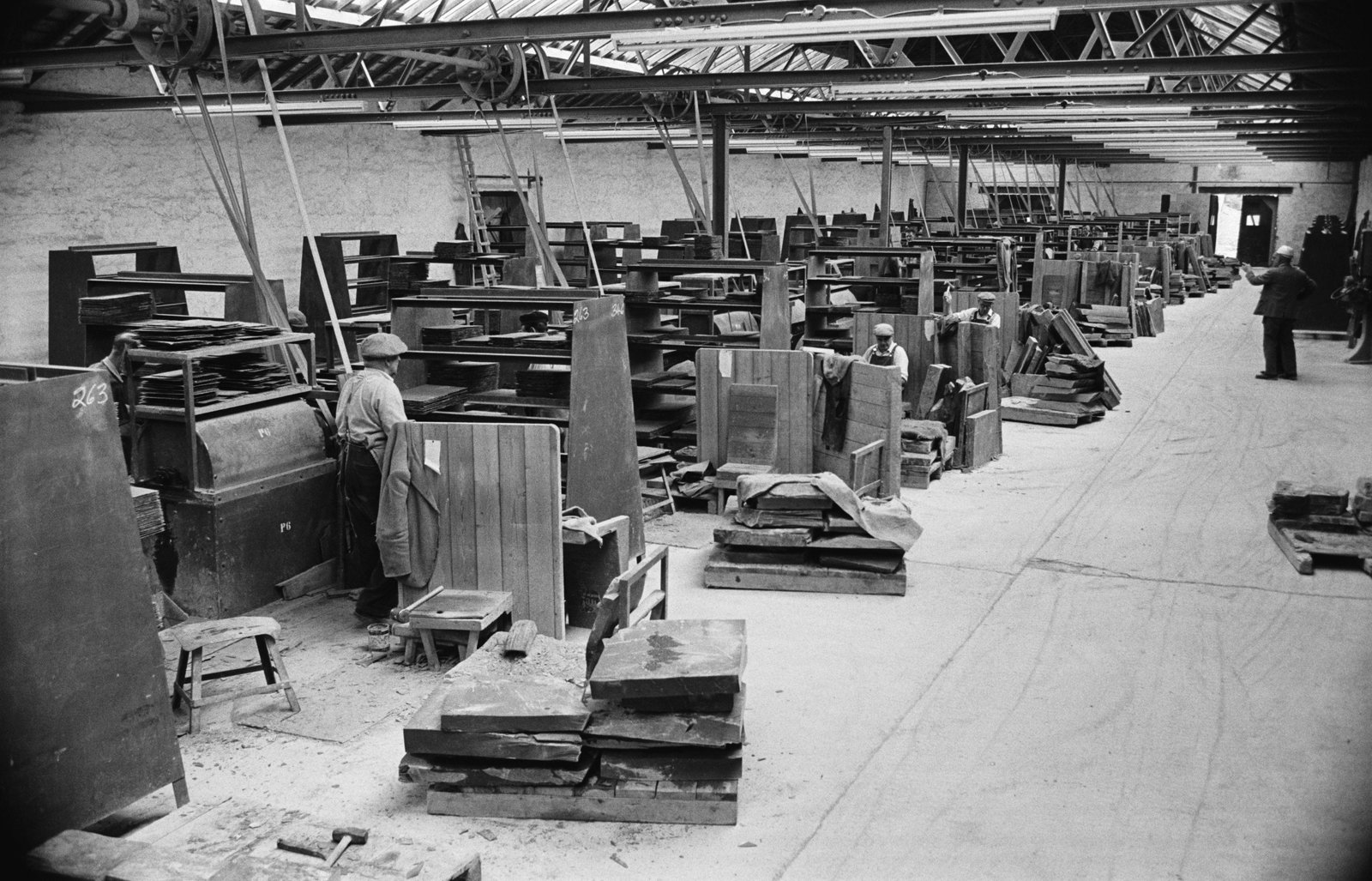

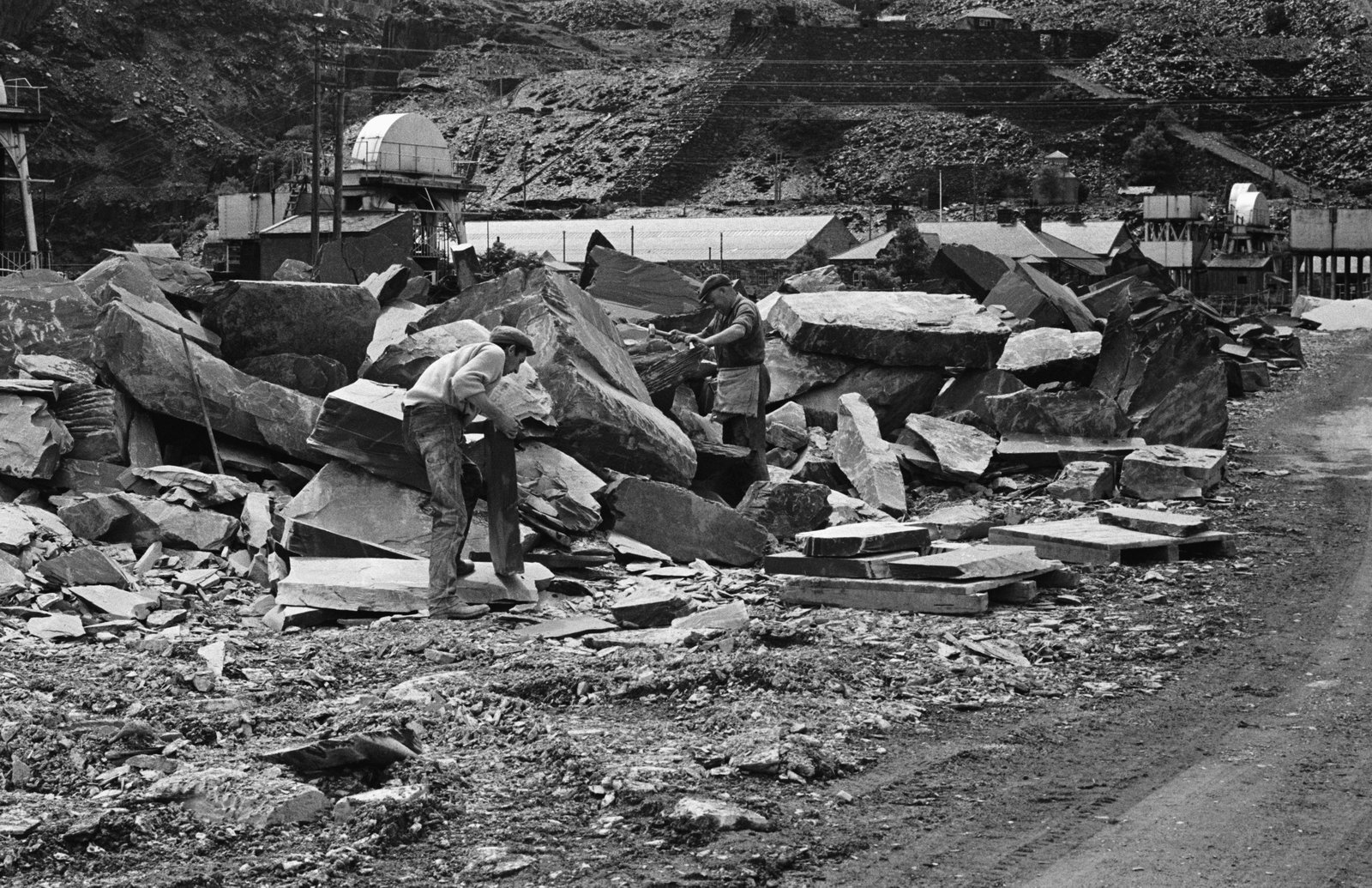

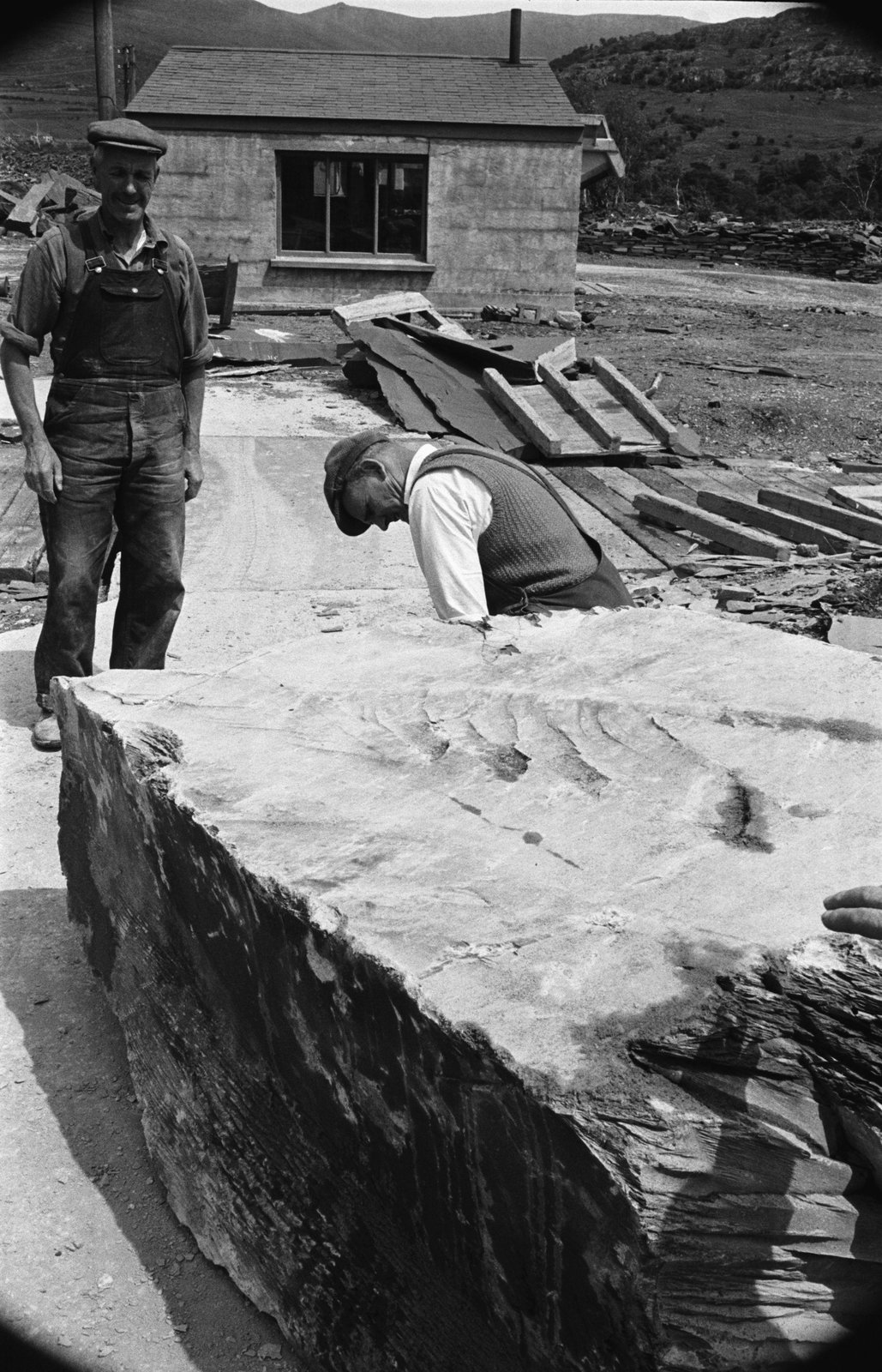

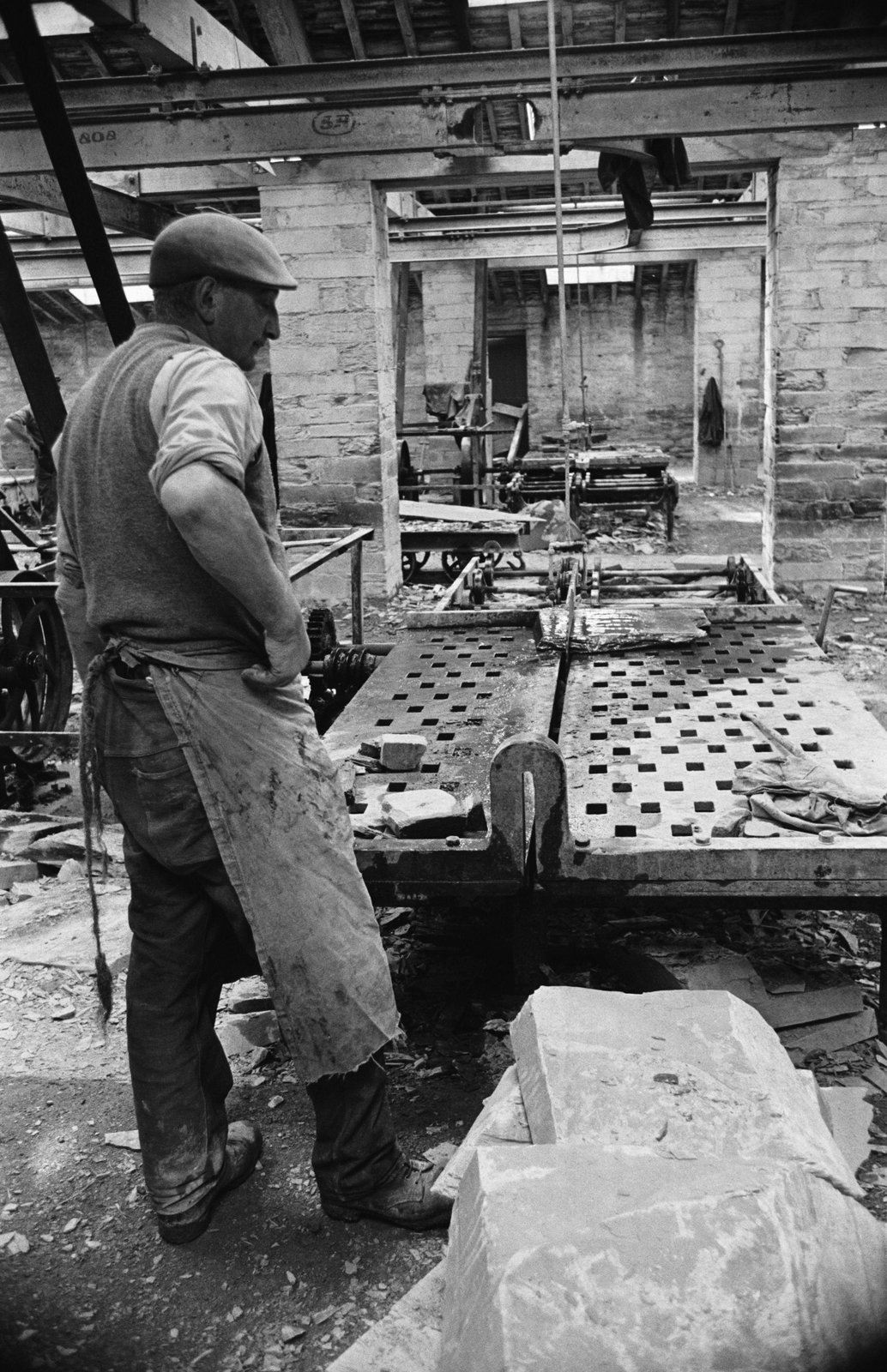

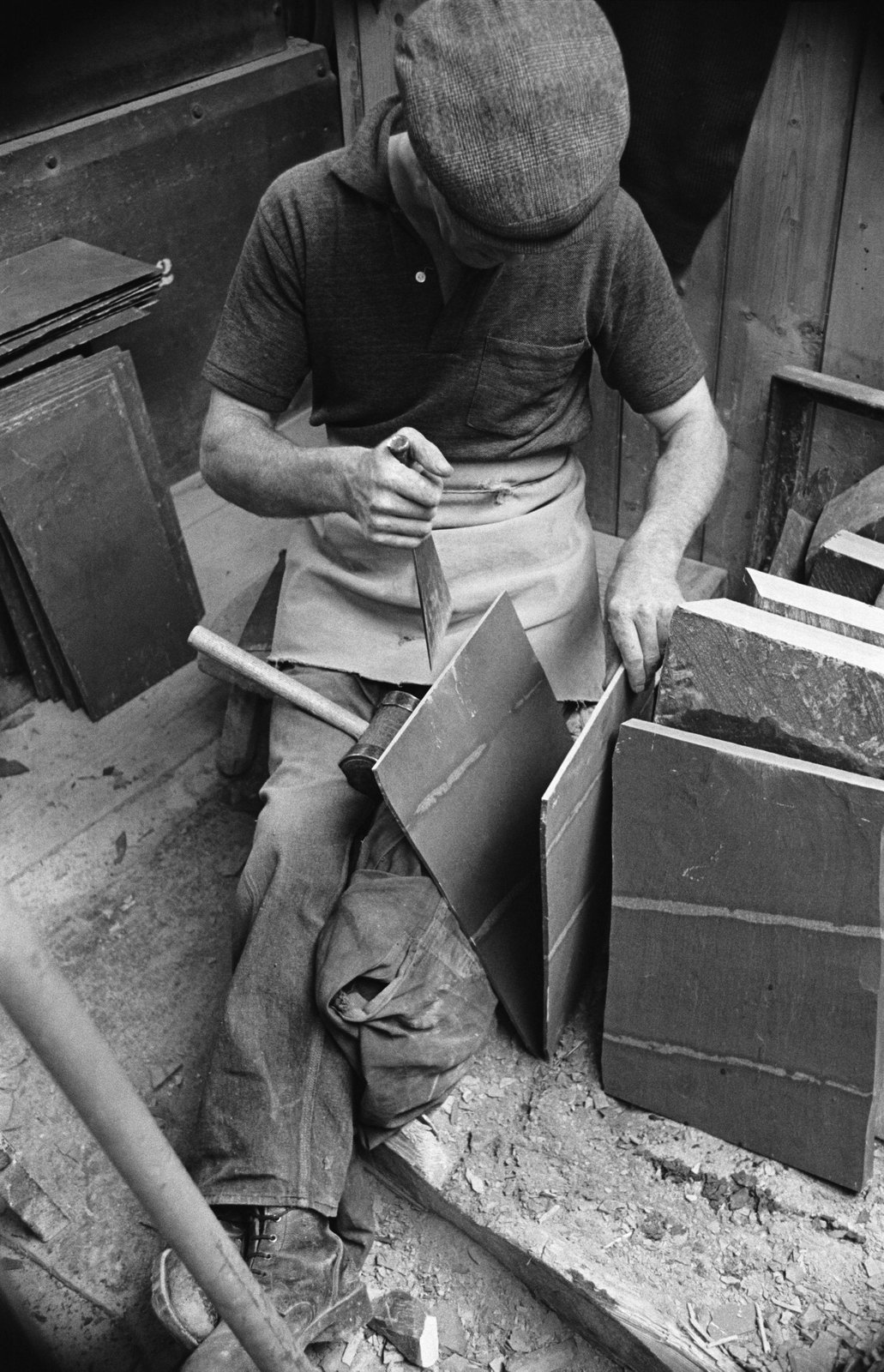

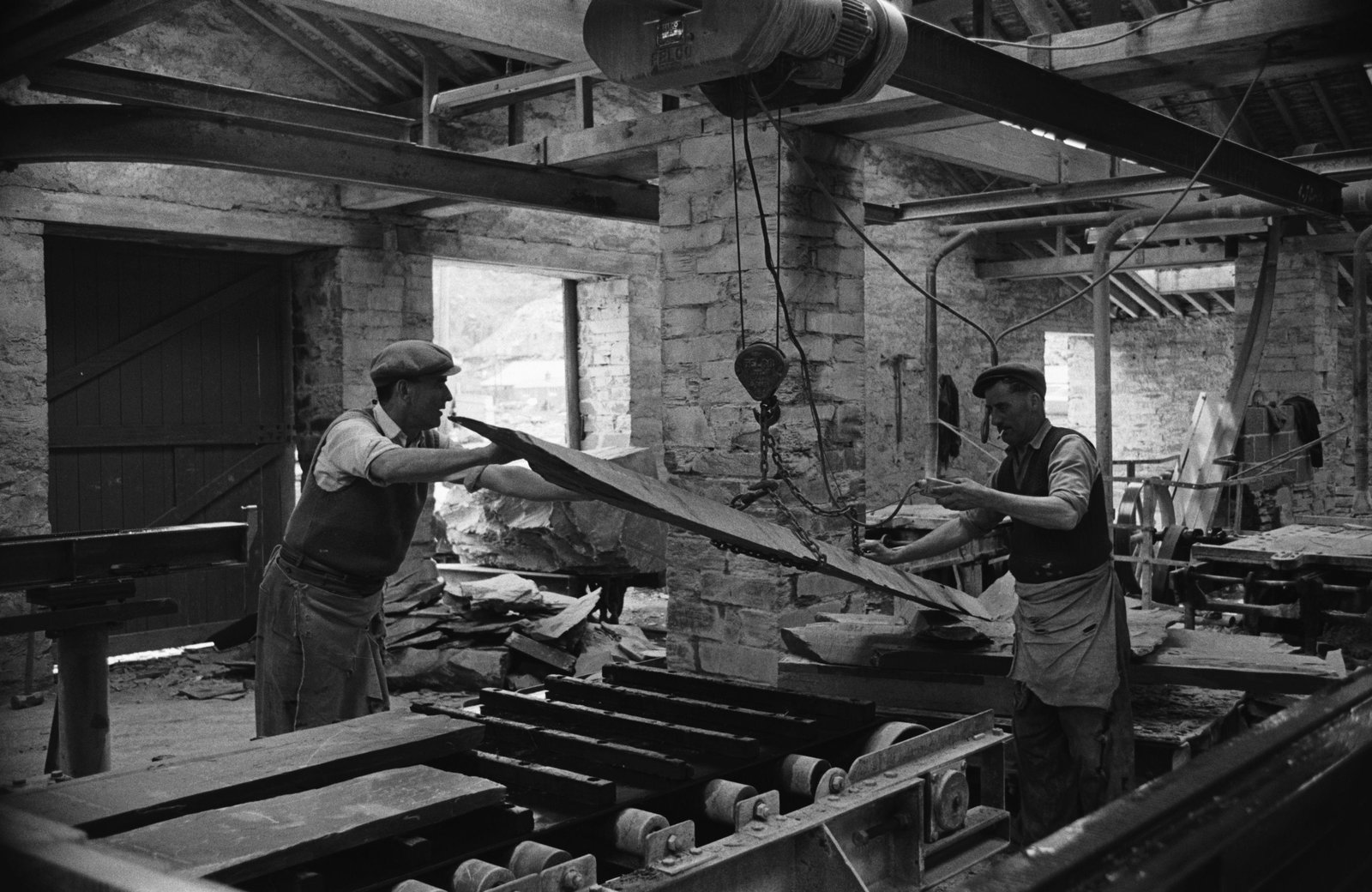

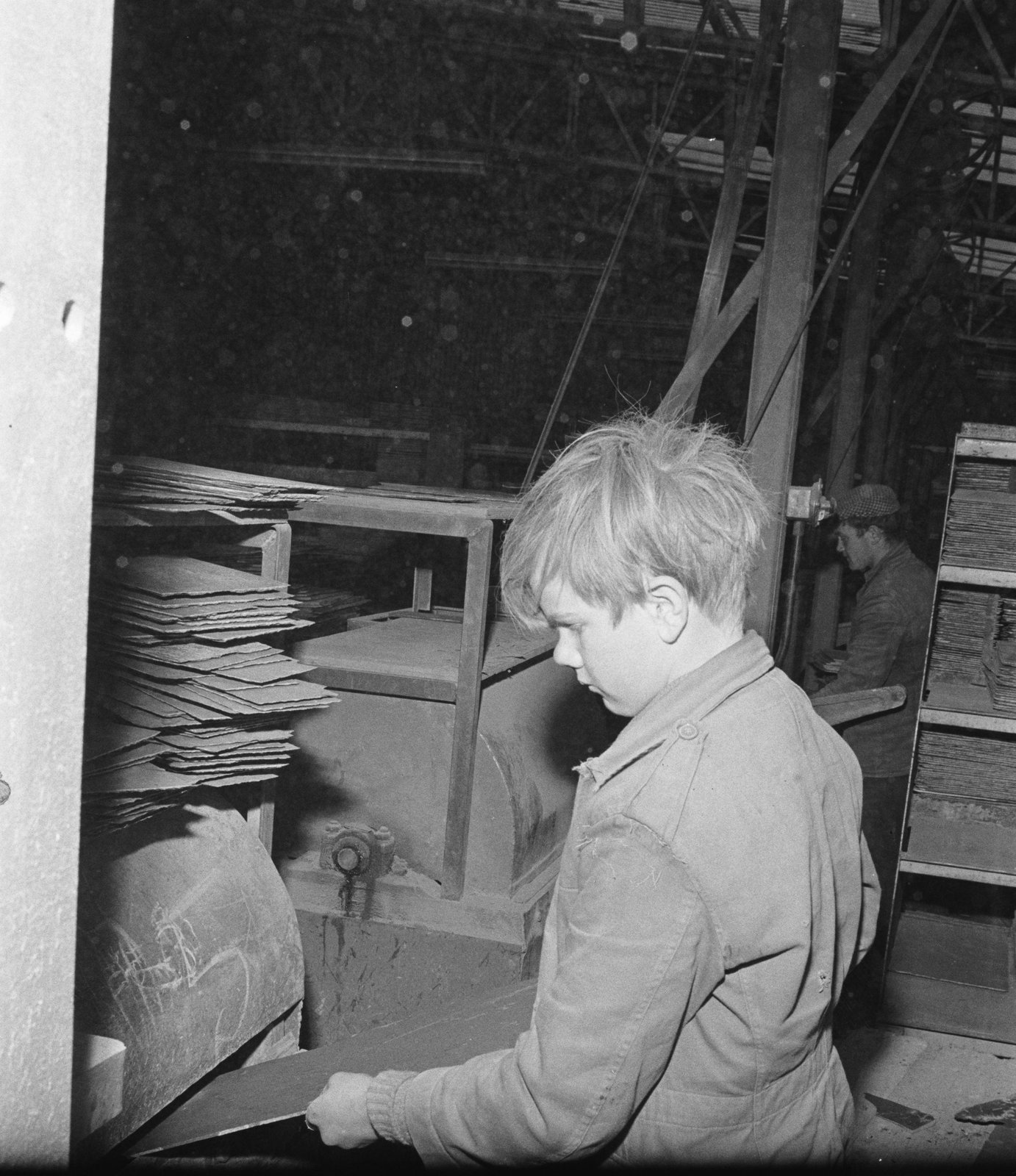

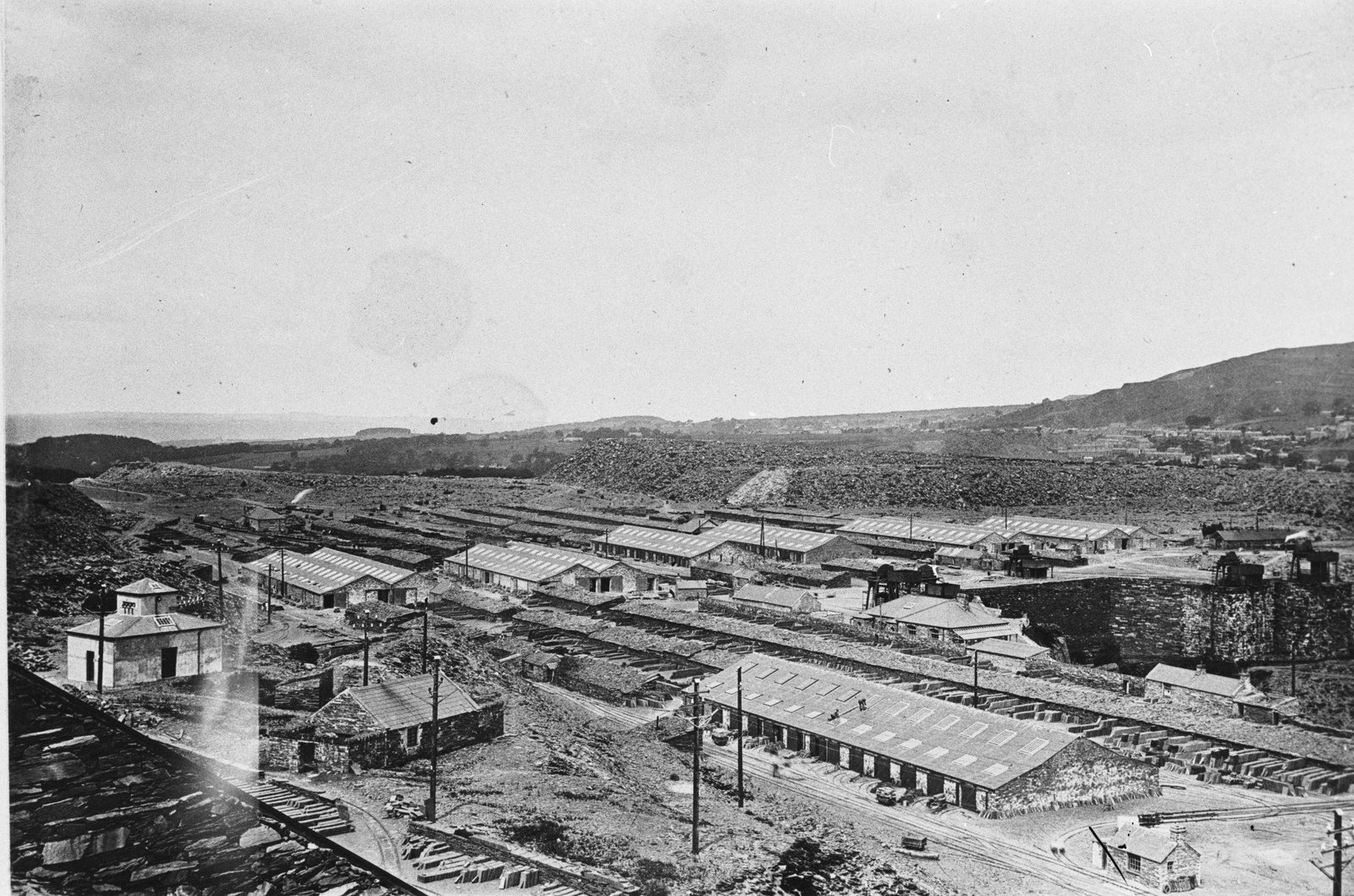

Initially, all slate dressing was performed by hand directly on the galleries. Machine sawing was introduced in the 1830s, and by the 1850s, work was consolidated into several large mills, powered by water, steam, and eventually electricity. While machine dressing was common, it was never as widespread here as in areas like Ffestiniog. It wasn’t until 1912 that roofing slate was sawn, meaning there were extensive “streets of wallia” (dressing sheds) adjacent to the mills for hand-dressing.

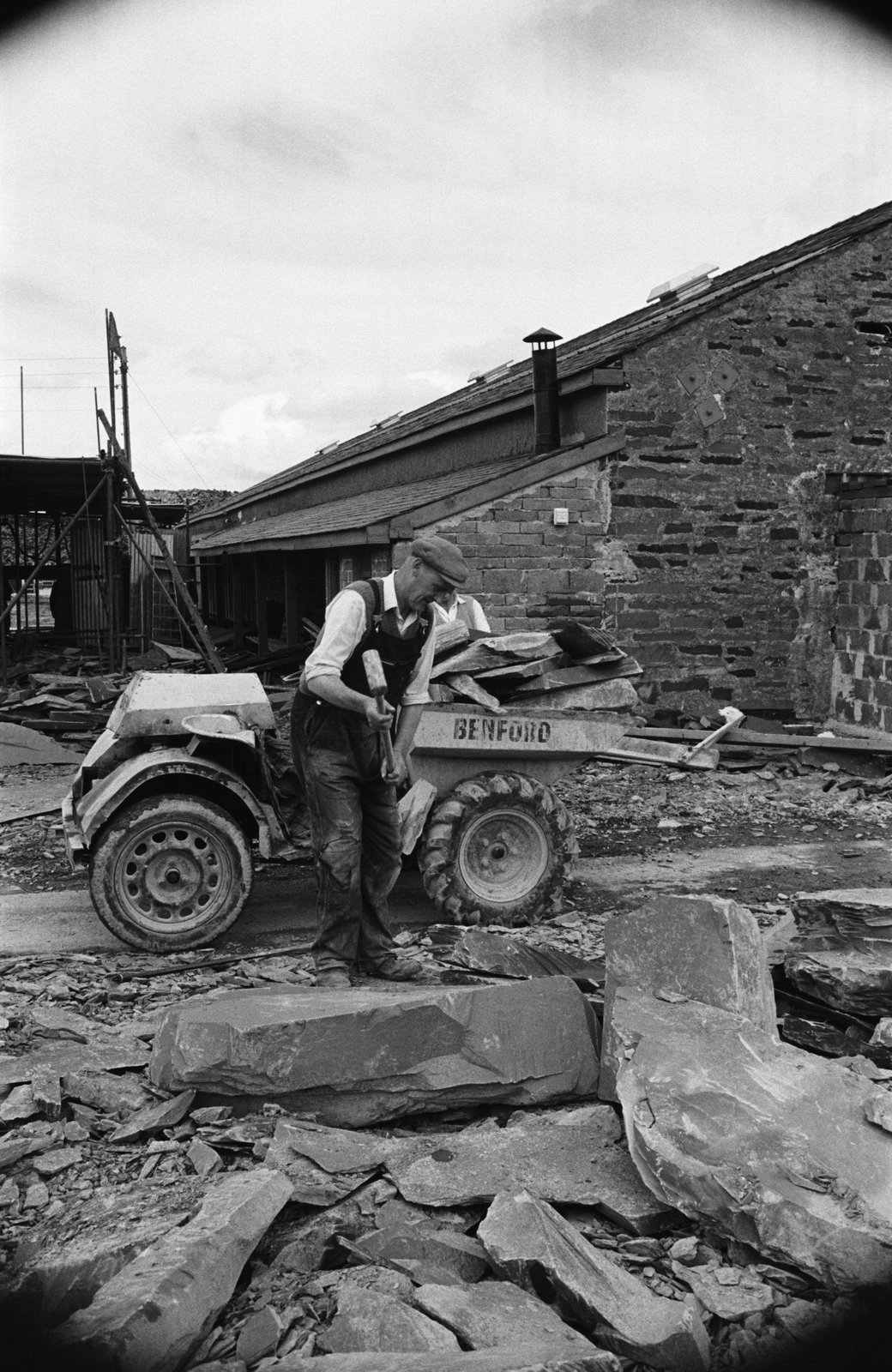

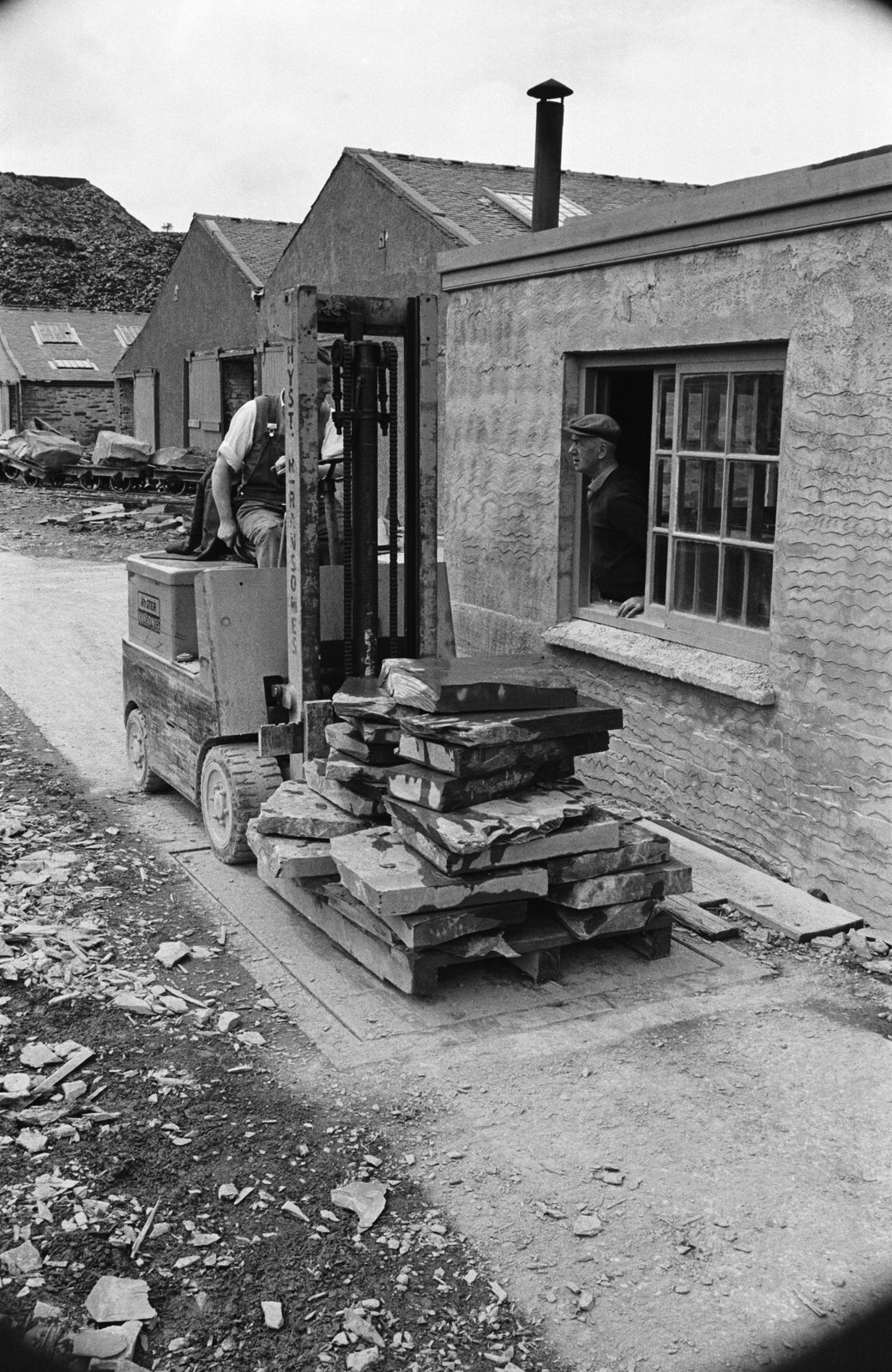

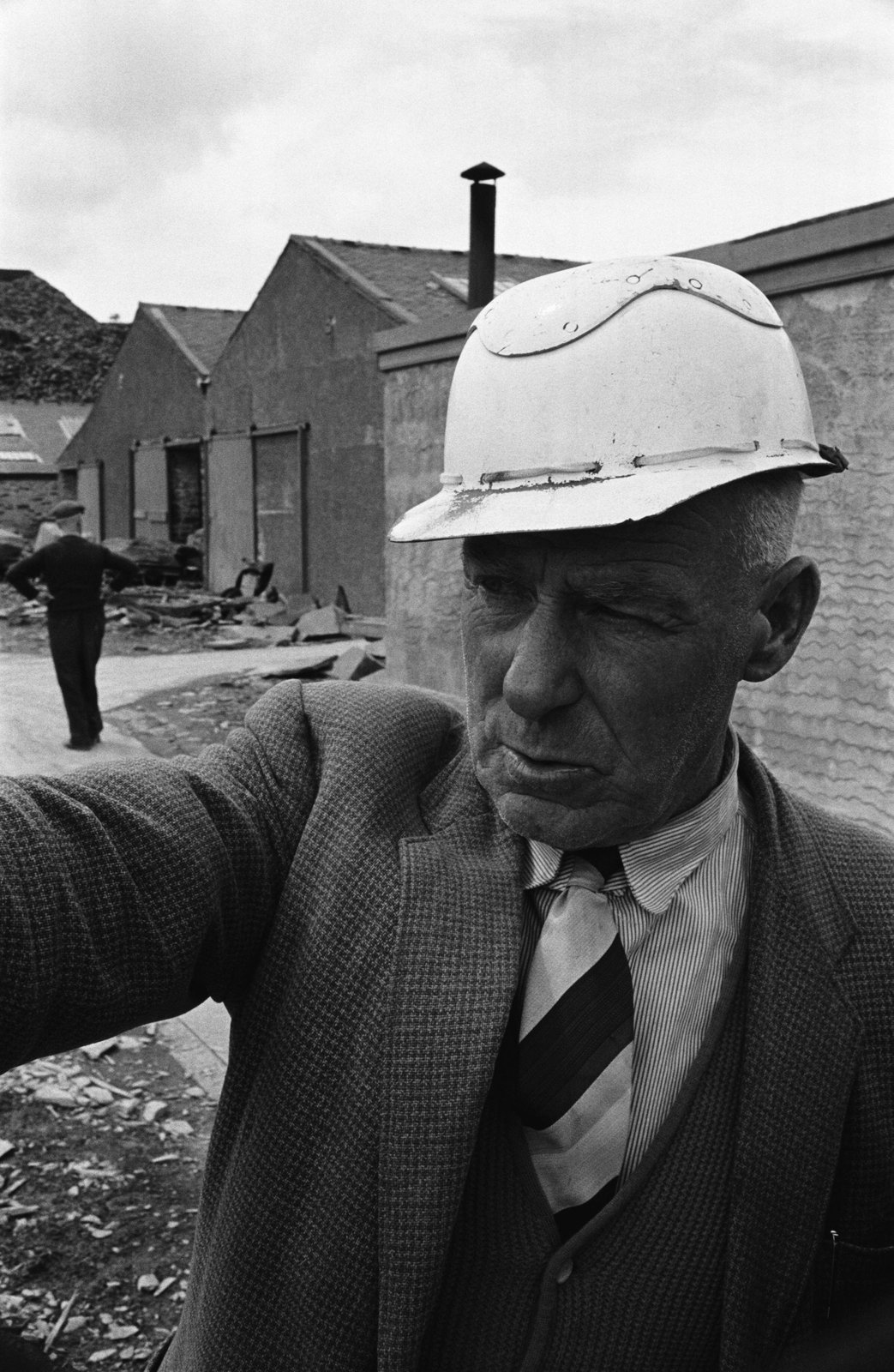

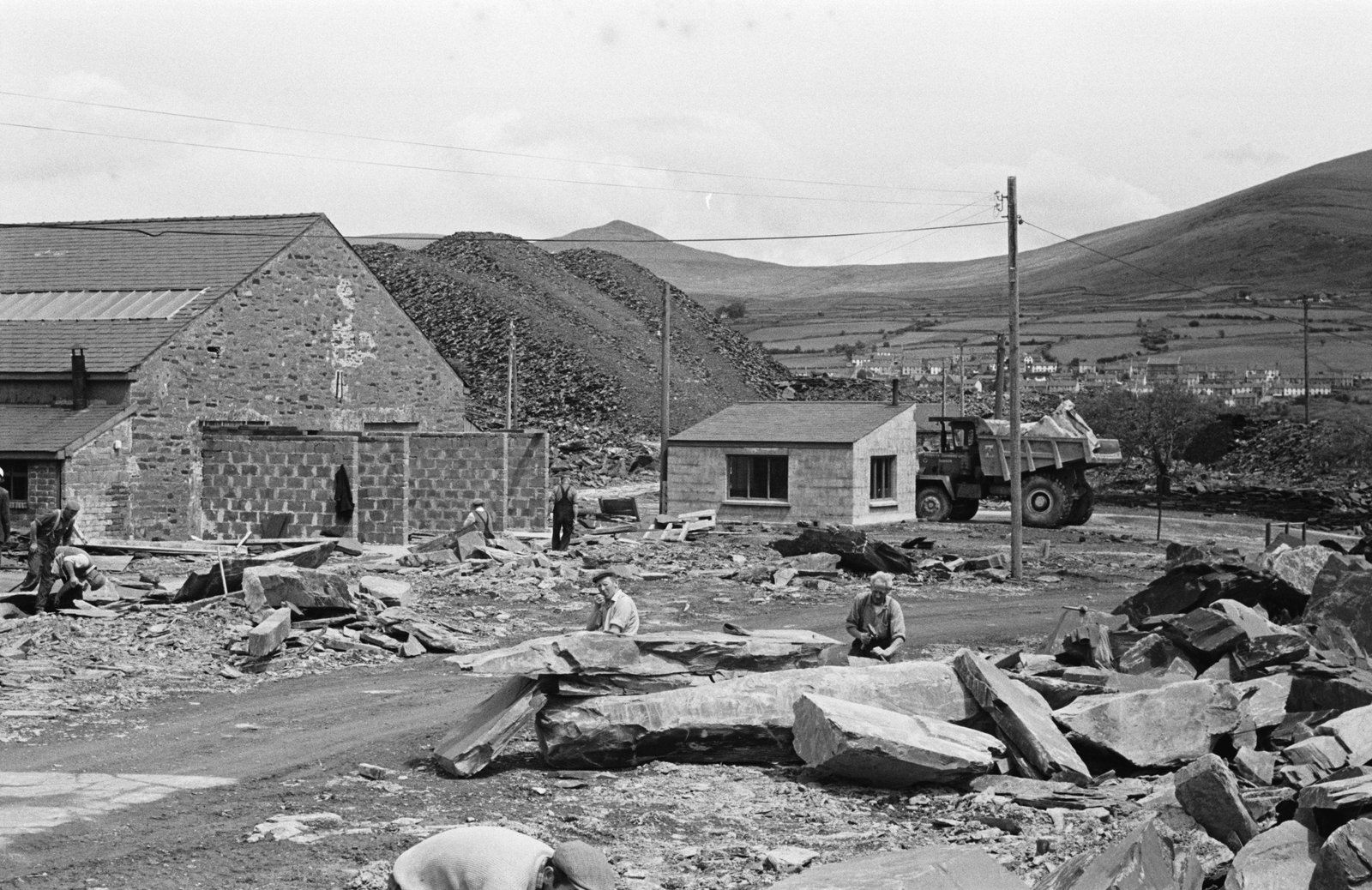

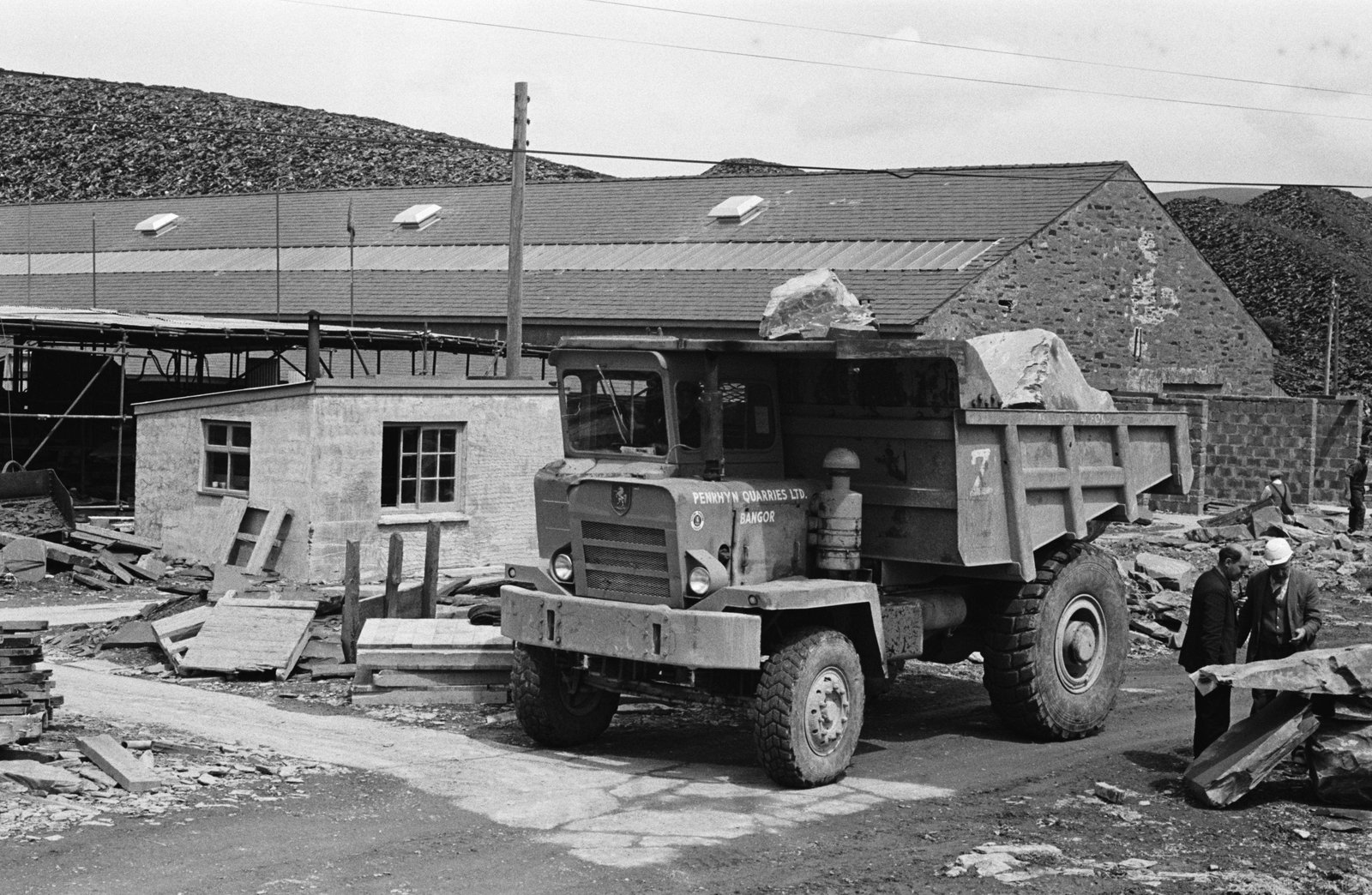

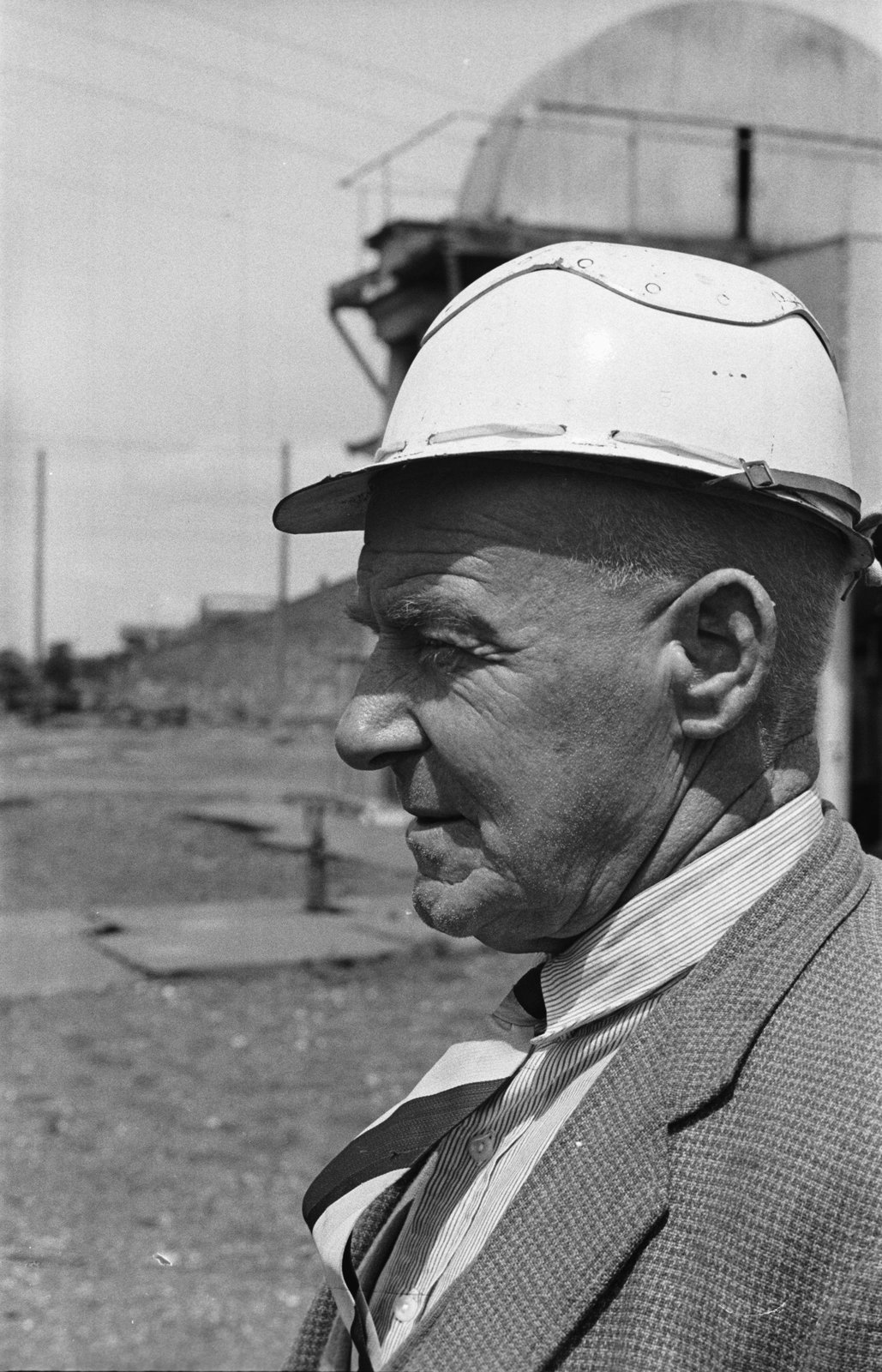

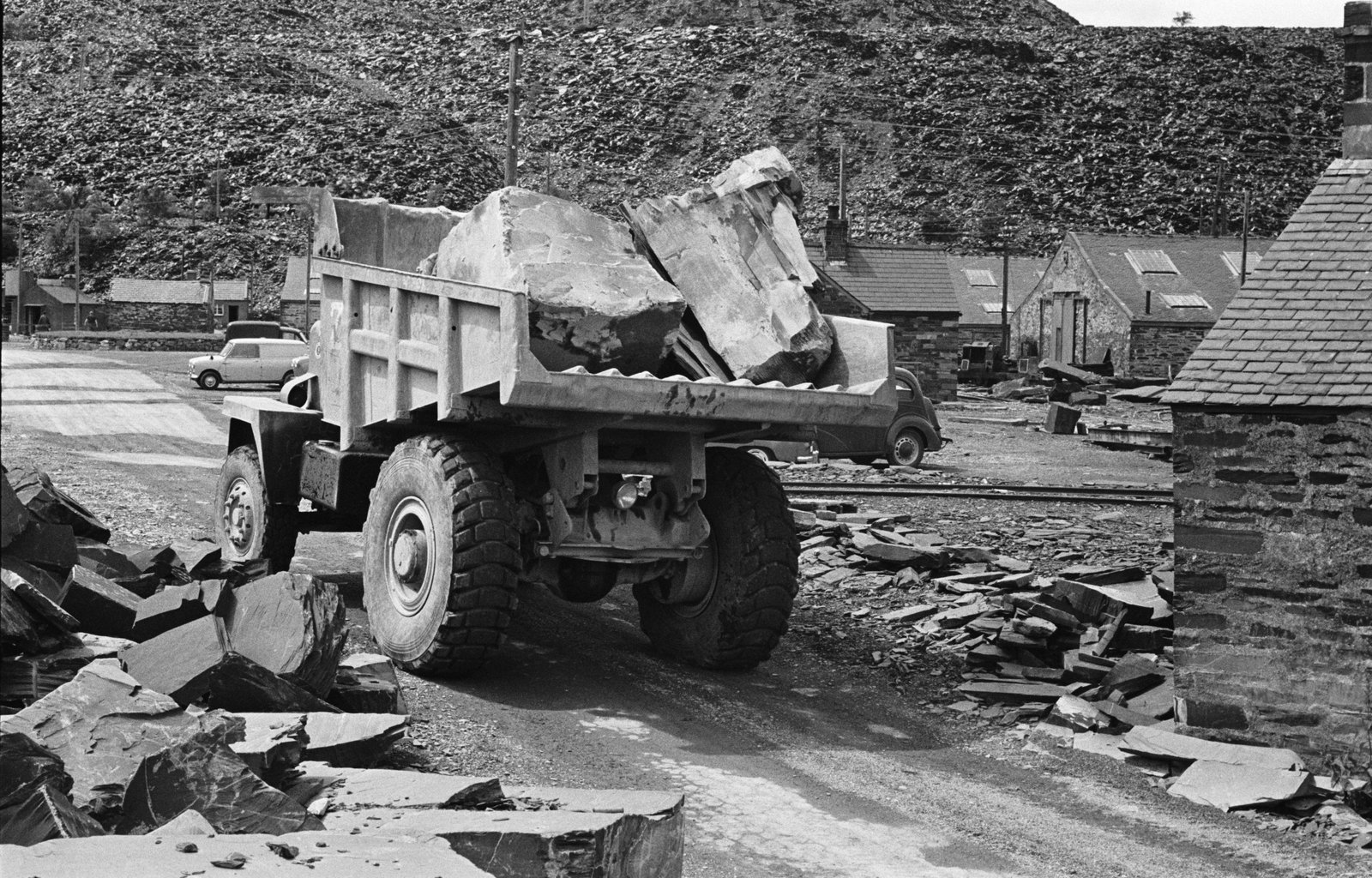

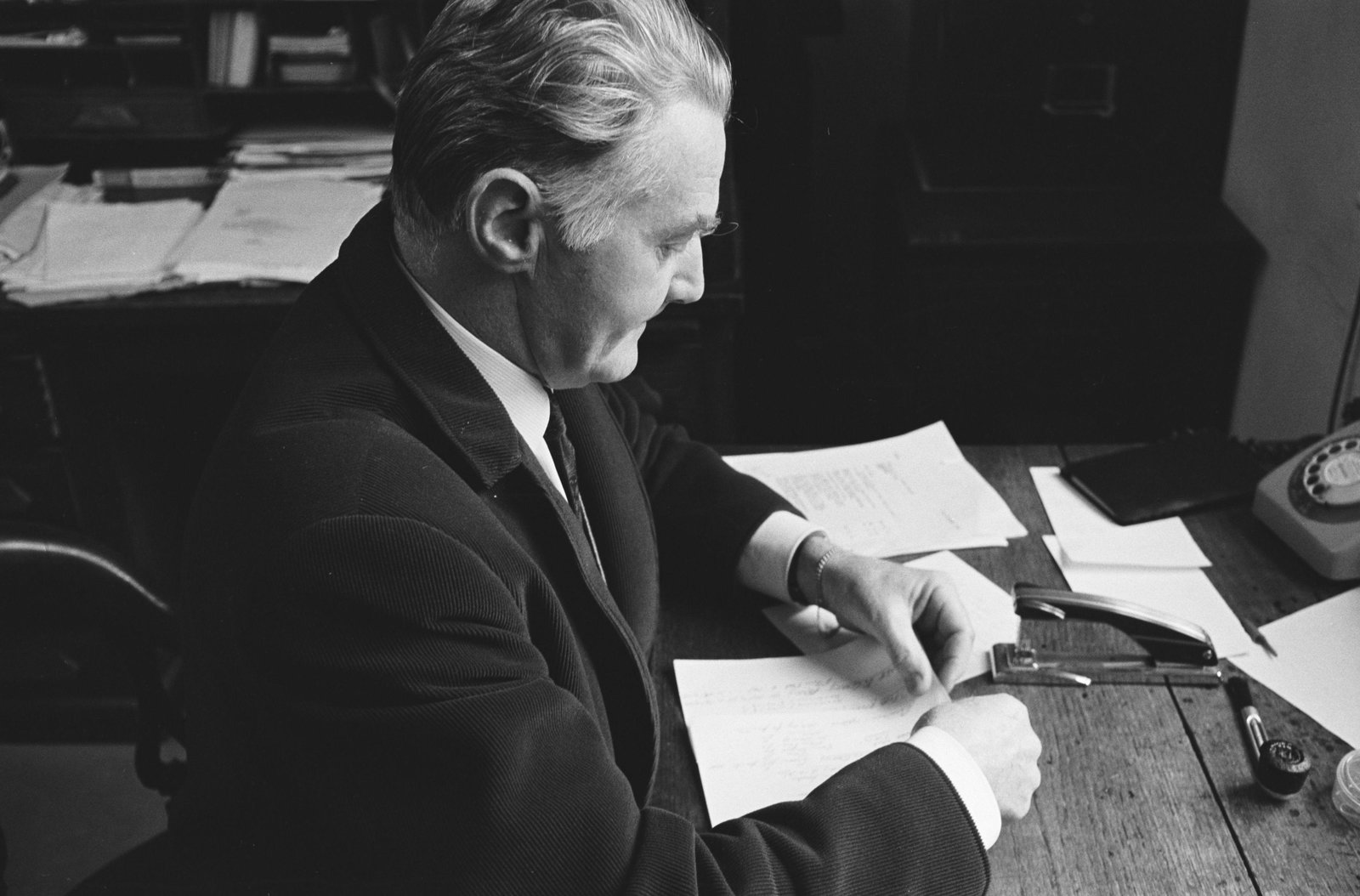

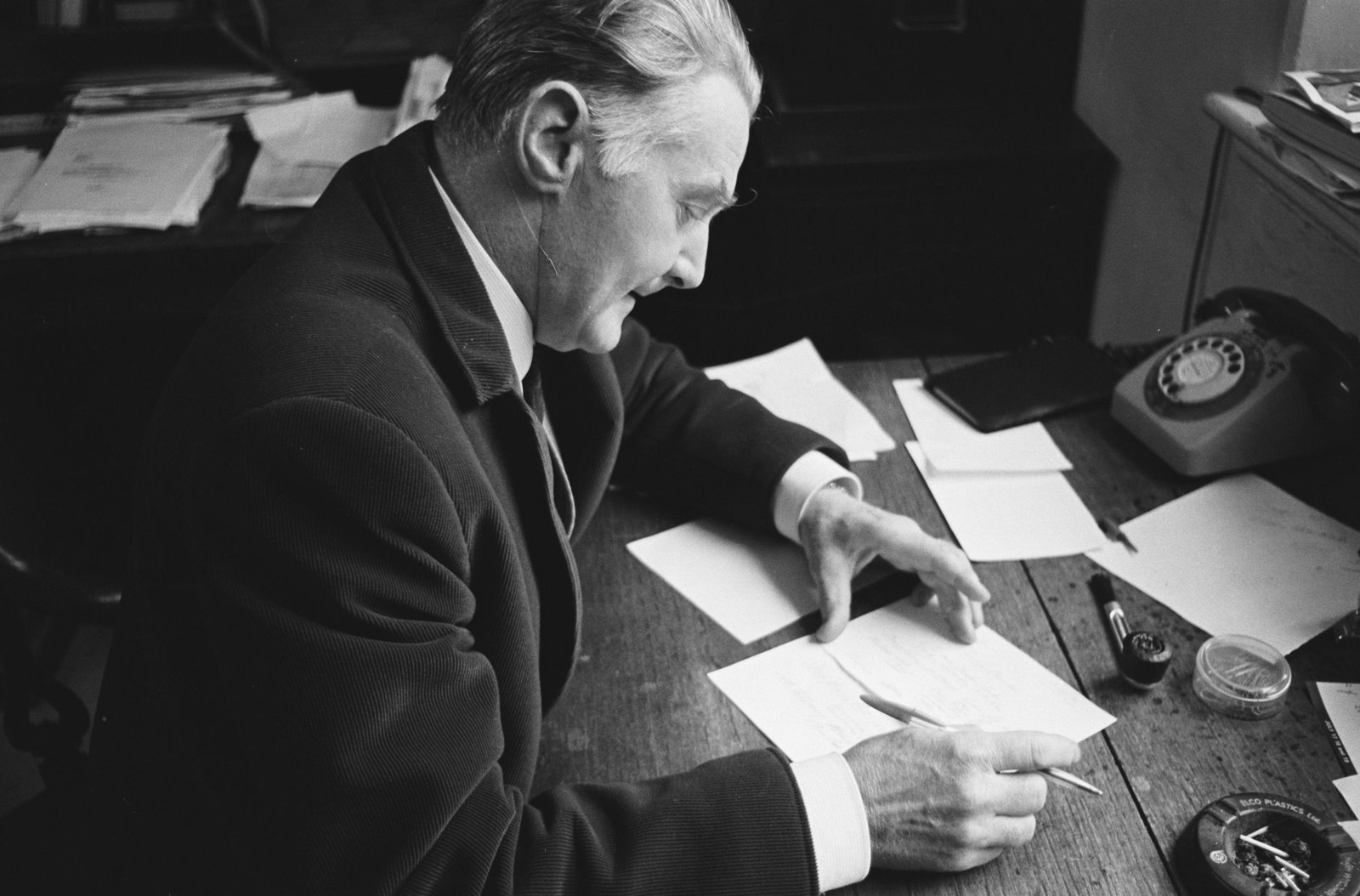

Today, quarrying still continues, with all on-site movement handled by dedicated transporters and fork trucks. While the old office remains in use, the mills area features entirely new structures. The present mills complex, located on the site of the old Red Lion mill, boasts the latest machinery, including an ‘all-sawing’ production line that eliminates manual splitting and handling, a development that makes Wales a world leader once more in slate-working methodology.

The modern bulk workings and road construction have significantly disturbed the overall quarry area. However, remains of several inclines and drum houses and a number of old buildings are still extant. The vigorously worked southern section though, retains little of the old structures. Separated by a great bank of modern waste, the currently disused and partially flooded northern section preserves much of its precipitous terracing and some structures intact. One of the unique water balance lifts is preserved near the main office, with one or two others remaining on-site.

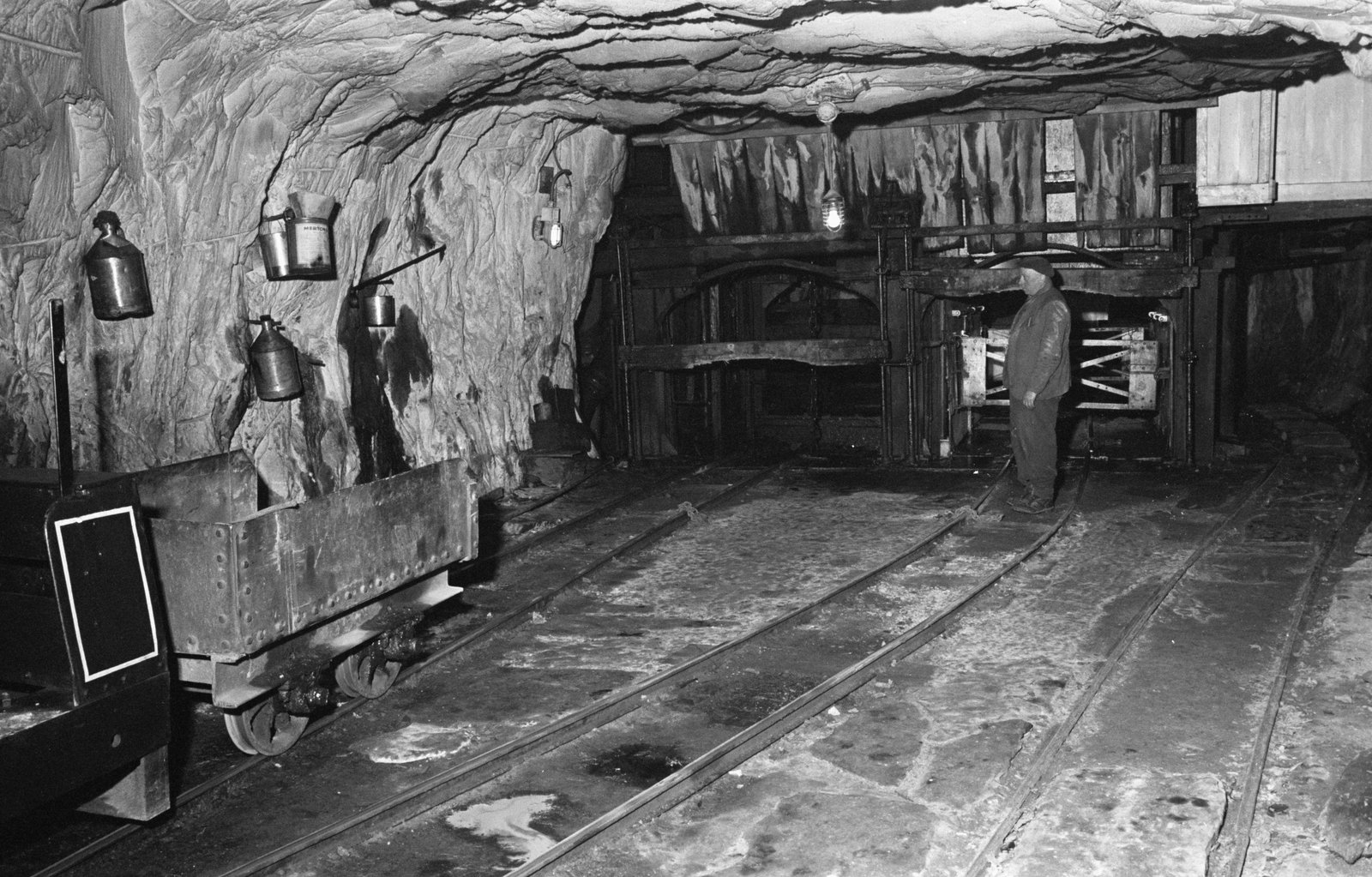

An important part of the complex was Coed y Parc (SH615663), which served as a concentrated industrial area. This was the terminus for both the Penrhyn tramway and the later railway, housing slate mills (the first dating from 1803), workshops, and several buildings in fair condition. Remains here include waterwheels fed by inverted siphons. The Ogwen Tile Works across the road, later a slate mill, is now in industrial re-use.

Worked since at least the 16th century. However, the modern undertaking dates from 1782, when Richard Pennant purchased the existing leased workings. Within just ten years, the quarry’s output, measured in five-figure tonnages, came to dominate the slate industry. By the latter part of the 19th century, annual production routinely hovered around 100,000 tons (peaking at 111,666 tons worked by 2,089 men in 1882). Apart from Dinorwig, Penrhyn was several times the size of almost every other quarry in Wales.

The enormous scale of the operation required significant logistical development. Before the establishment of Porth Penrhyn as a harbor in 1790, slate was carted to Bangor for shipment. The new harbor, which also became the site of a writing slate factory, greatly streamlined transport. In 1801, the labor-intensive cartage system—which employed 140 men and 400 wagons—was replaced by the horse/gravity Penrhyn Railroad. This, in turn, was superseded by the steam-powered Penrhyn Railway in 1878. Further connectivity was achieved after 1852 with the opening of the Porth Penrhyn branch from the London and North Western Railway (L&NWR) main line, allowing an increasing tonnage to be transferred directly to the national rail network instead of being shipped coastwise.

On-site transport also evolved: steam locomotives were introduced in 1876, followed by internal combustion (i.c.) power in the 1930s. However, by 1964, all locomotives had been replaced by lorries. Extensive electrification of the site began in the early 20th century.

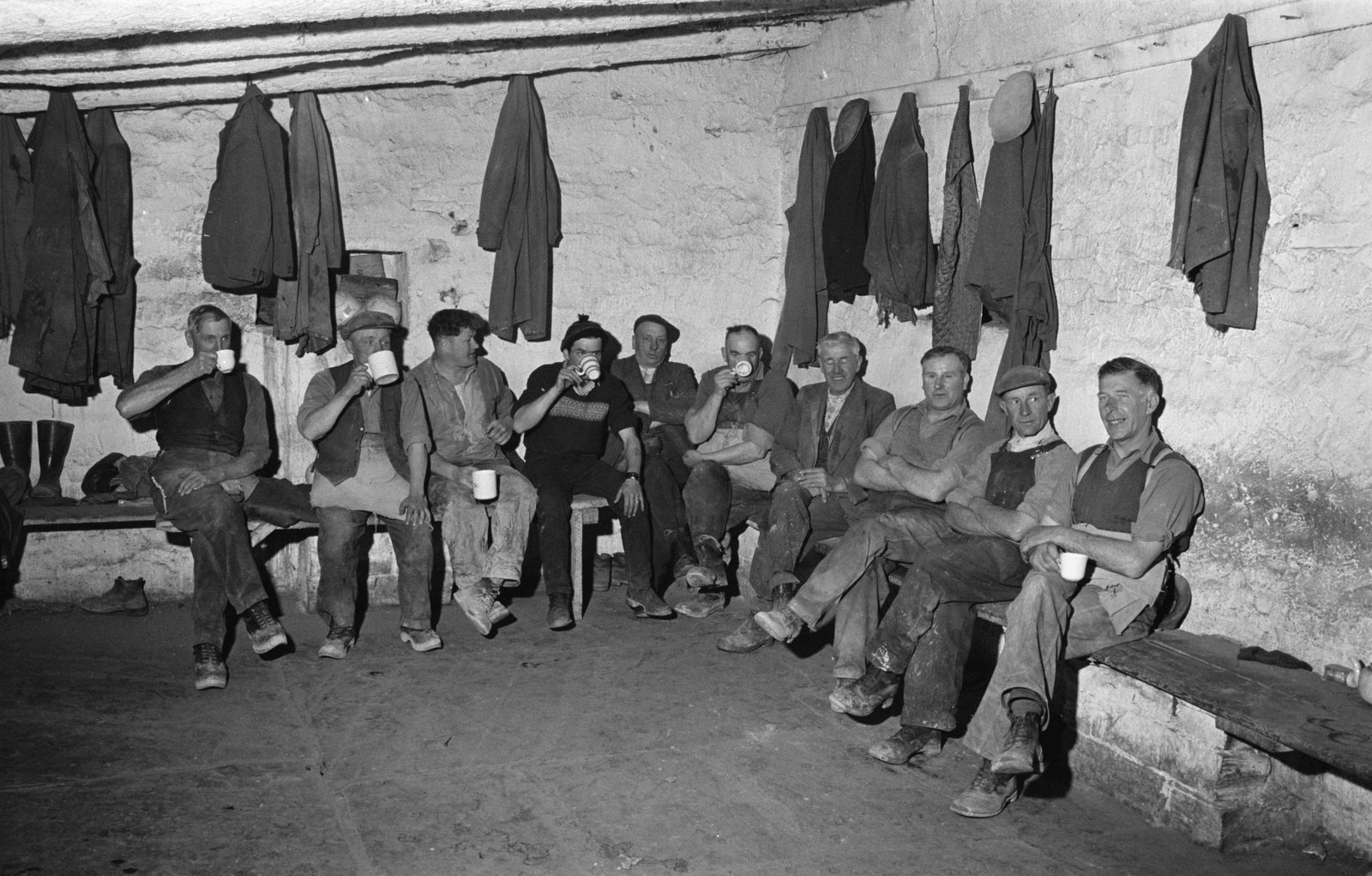

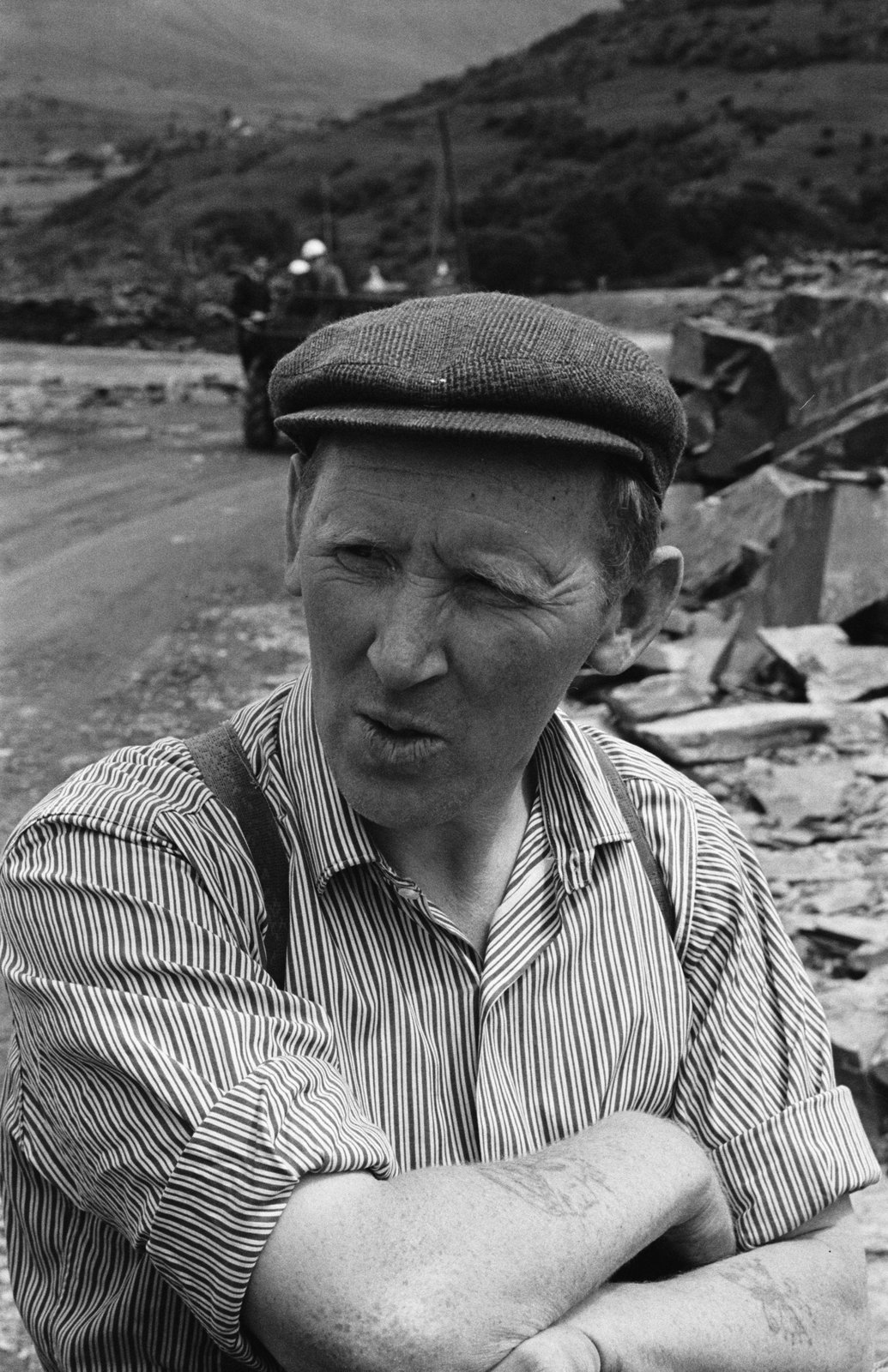

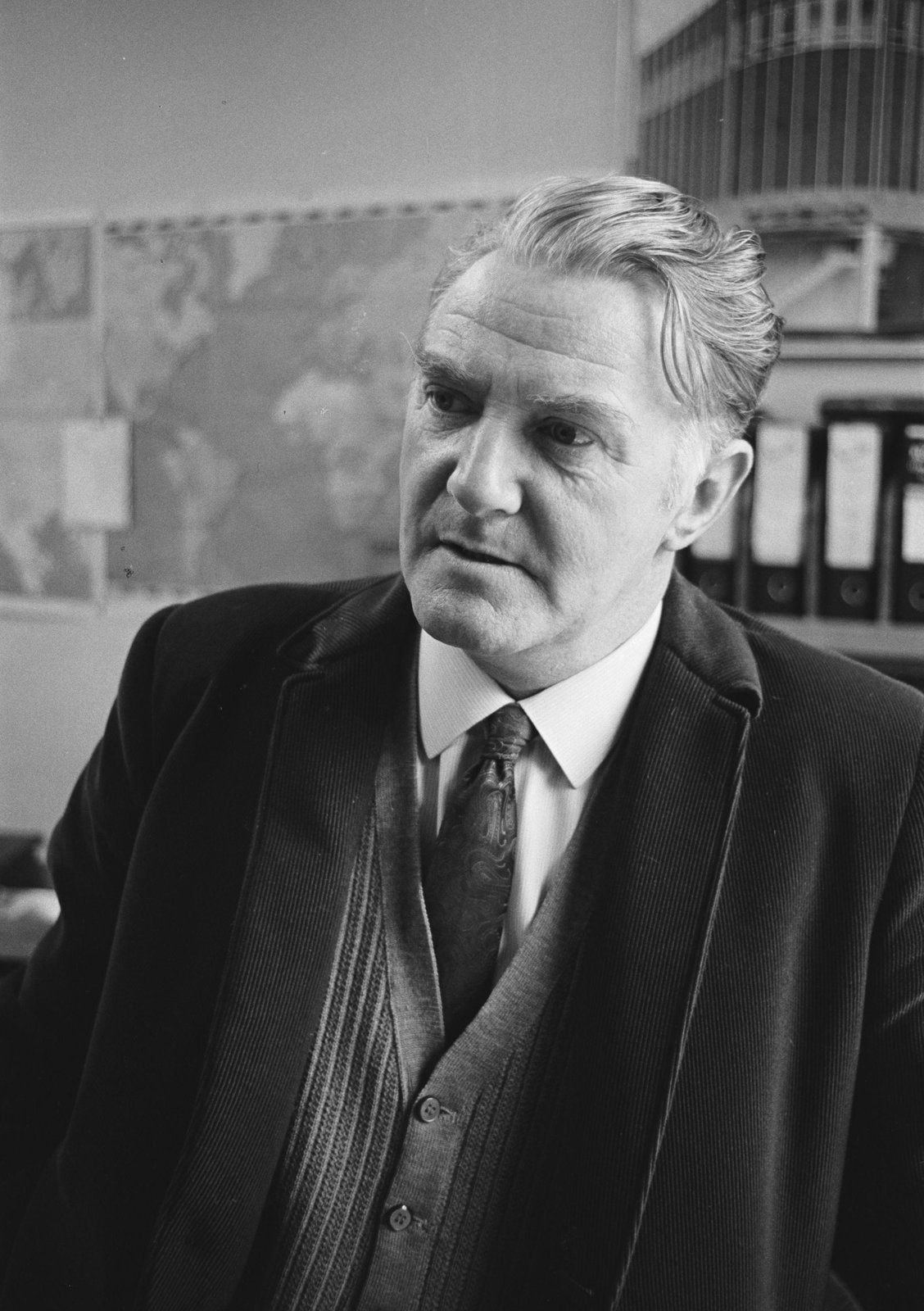

The 1900–1903 Great Penrhyn Strike was Britain’s longest industrial dispute. Lord Penrhyn refused to recognize the quarrymen’s union (NWQU), leading 2,800 workers to strike for three years. The struggle caused extreme hardship and community division. Ultimately defeated, the workers returned on Lord Penrhyn’s terms, though the strike secured its place as a key event in British labour history.

Publications (23)

- (1982); WMS Newsletter Issue 07 Dec; 3 pages

- (1991); WMS Newsletter Issue 24 Jun; 4 pages

- (1995); WMS Newsletter Issue 32 Jun; 7 pages

- (1997); WMS Newsletter Issue 37 Dec; 11 pages

- (1999); WMS Newsletter Issue 41 Nov; 16 pages

- (2002); WMS Newsletter Issue 46 Apr; 23 pages

- Anon (1912); Penrhyn Quarry Blondins; 1 pages

- Anon; Penrhyn Balances Map; 1 pages

- Anon; Penrhyn Map; 1 pages

- Anon; Penrhyn Quarry Floors; 1 pages

- Ball, Lionel C. (1909); Penrhyn Quarry - Queensland Govt. Mining Journal; 4 pages

- Ball, Lionel C. (1909); Queensland Government Mining Journal - Elsh Slate & the Penrhyn Quarry; 4 pages

- Jarratt, Tony (1981); Logbook 2; 121 pages

- Knowles, Jon (2008); Penrhyn Slate Quarry - Underground Features; 28 pages

- le Neve Foster, C. (1896); Mines & Quarries Report-North Wales; 57 pages

- NMRS; British Mining 34 - Memoirs 1987; pp.31.

- NMRS; British Mining 88 - Memoirs 2009; pp.20.

- NMRS; Newsletter Feb/1988; pp.4-5

- NMRS; Newsletter Nov/1989; pp.2

- Owen, Elias (1885); Penrhyn Quarry- Red Dragon; 12 pages

- Richards, Alun John (1991); Gazeteer of the Welsh Slate Industry, A; Gwasg Carreg Gwalch 978-0863811968

- Richards, Richard (1868); Penrhyn Slate Quarry; 3 pages

- Williams, C.J.; NMRS (1995); British Mining 52 - Great Orme Mines, The; ISBN 0901450 39 1; pp.21.